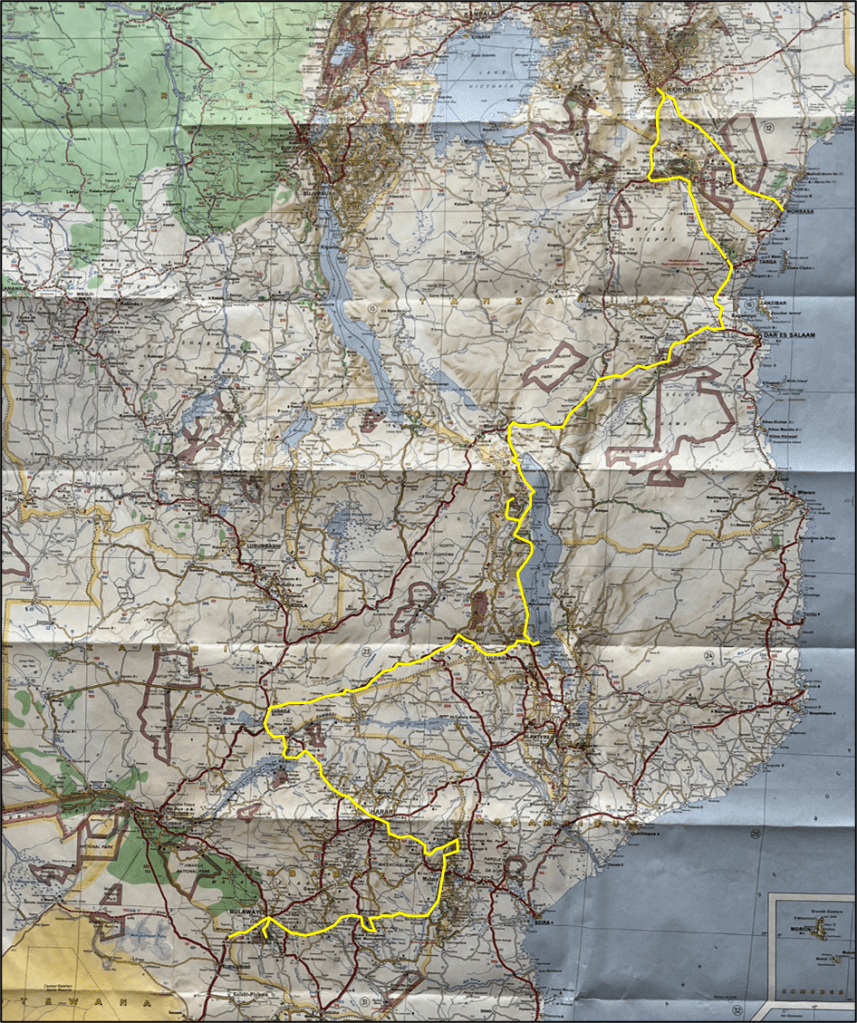

Route map

Zimbabwe

We leave Francistown and clear the Zimbabwe border at Plumtree 50 miles north-east.

We have worried for months about this stretch through the Matabeleland to Bulawayo with the horror stories of kidnappings and murders. Things have been quieter for the six months since the Zanu-Zapu pact but we resolve not to have a single stop nevertheless. Zimbabwe is a contrast to the rest of Africa and sometimes seems scarcely part of it. The towns are a cross between 1960s Britain, cars and roadsigns, colonial British Columbia, street layout and architecture and the sanitised efficiency of a Germany or Austria. Africa only manages to creep in in the countryside or the large native markets in the towns. The people are as friendly as any we have met on our trip. Nearly everywhere outside Britain motorcyclists are welcomed but this place is ridiculous. We are shown round towns, provided with cups of tea and offered places to stay for the night. The hard edge has gone from the trip and we feel guilty as if we are on a long holiday. I have never been to a country before where every town has a campsite with free hot baths!

Bulawayo and the Matopos Hills

Bulawayo boasts one of the world’s finest museums with superb exhibitions of natural history, geology and recent Zimbabwe history.

The town is laid out in a grid running from 1st to 14th Avenue. The major avenues were designed to be wide enough to turn a full train of eight oxen and prove just about adequate for the old gas-guzzling Fords and Chevrolets that continue to roam the streets.

The railway station dates back to the turn of the century and has been crucial to the development of southern and eastern Africa. Everything funnelled through Bulawayo – cattle, minerals, crops troops and settlers. Coal is Zimbabwe’s cheap power source and has assured the continuation of the steam train.

There is a daily service to Victoria Falls which chugs out at 7pm exactly. The carriages are 1952 vintage and are brightly painted in the browns and yellows of the National Railways of Zimbabwe.

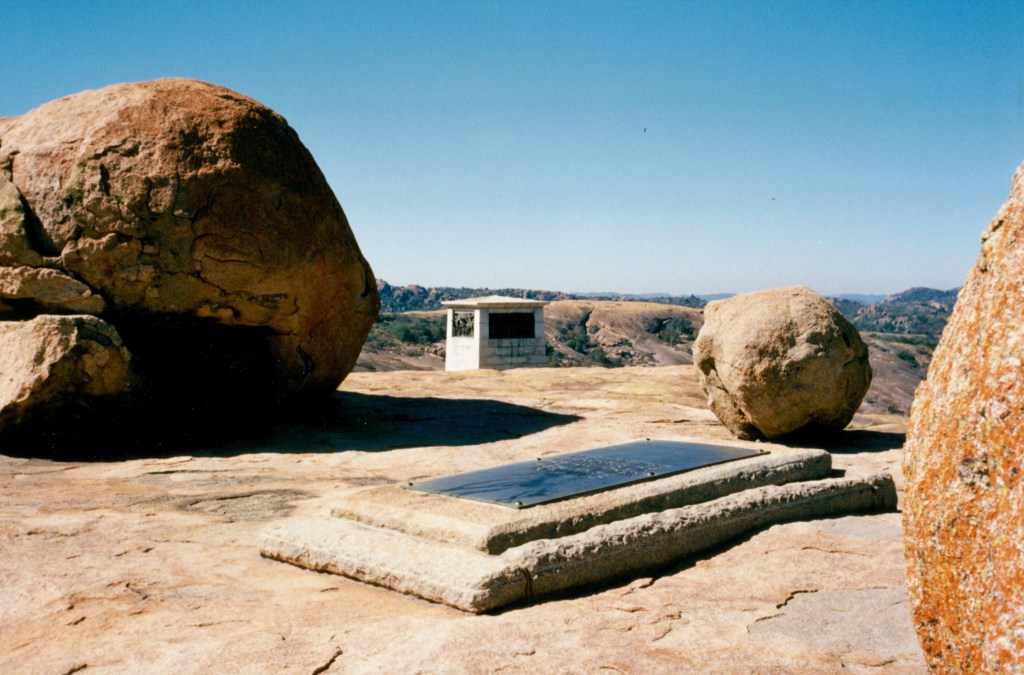

South of Bulawayo lies the Matopos range. Bare, craggy limestone hills rise mysteriously from the heart of the Matabeleland. Erosion and faulting have left enormous stones balanced implausibly on top of hills.

High up at the World’s View lies the grave of Cecil Rhodes whose body was brought all the way from Cape Town to lie in this his favourite place.

His tomb is a simple rock slab and contrasts sharply with the gaudy mausoleum built nearby to commemorate the deaths of Rhodes’ friend Alan Jameson and his band of freebooters at the turn of the century. Close to here are cave paintings dating as far back as 4,000 years. Designs of cattle, elephant and various antelope were finely painted with a mixture of blood, milk and wine.

Unfortunately, Kilroy has been here too and every site is guarded closely. From Bulawayo we head south through flat and featureless grasslands. The main road occasionally runs parallel to the old and now abandoned tar – strip roads which were built by unemployed white people during the depression of the 1930s. Many thousands worked in the gangs which built roads consisting of two strips of tar a car’s wheelbase apart. The middle and sides remained dirt only being filled in with tar on bends. Passing on these roads involved both cars having one set of wheels on the tar only. These roads remained in use for over thirty years and were unique to the then Rhodesia and were marked specially on Michelin maps even into the 1960s.

The Great Zimbabwe

Close to Masvingo are the Great Zimbabwe ruins which are Africa’s equivalent to the dry stone wallers of Mycenae. The origins of the ruins appear unclear but building appears to have commenced in the 14th century. The area was abandoned two hundred years later when the surrounding country had become overused and infertile. Its founders were farmers and traders in pottery, gold and other minerals. Artefacts from the Middle and Far East have been found on the site as well as objects from East Coast Africa.

There are three main parts to the site. On top of the huge kopje, a smooth, rounded hill, with a superb command of the surrounding plains is a fortress with well-built battlements which supplement its natural stone defences. There is a maze of tiny corridors and buildings around the hilltop. Back on the valley floor are the two largest enclosures. At one time connected by high walled paths the enclosures are themselves surrounded by walls up to thirty feet high feet and six feet thick. At the far end of one enclosure is a conical, narrowing storage tower which rises high above the walls. When discovered in the 19th century the site was excavated in a brutal and inaccurate fashion and many of the relics were removed. The site, however, remains mysterious and by evening the fortress appears stark and brooding in eerie silence silhouetted against the black night sky by a full moon.

The Eastern Highlands

From there we ride due east into the Eastern Highland range which marks out the border with Mozambique for over a hundred and fifty miles. At the southern end is the Chimanimani range, in the middle around Mutare are the Vumba Gardens and in the north, there is the Rhodes Inyanga National Park which includes Mt Inyangani at 8,500 ft the highest mountain in Zimbabwe. We spend some time touring around walking in these hills. Our last stop is at the Nyanga camp and that evening we drive over to the Rhodes Nyanga Hotel. We enter and ask for coffee or tea but are informed that they are not served much after dusk. We cannot go into the bar because we do not have ties. Just then the hotel manager who is about our age comes in immaculately dressed and we are sure that there will be no welcome at inn now. He, however, disappears and reemerges with two ties and we join him for his evening tea. He stays talking to us most of the evening. He is from Harare and has been here for about a year. Most of the hotel’s business comes from white people who are looking for an escape from the rat race of Harare and spend time fishing or walking mountains. Some people come up from South Africa. Very few are from Europe as the attractions are too similar to those available in Scotland.

It seems a curious backwater for someone so young to be in but he says has no time for the bustle of Harare or Bulawayo. He says that the border problems with Mozambique and Renamo do not affect people coming here for peace and quiet and are, therefore, irrelevant. He makes occasional trips to Mutare but that’s more than enough for him. We leave thrown by the evening unable to come to terms with someone our own age who, unlike with our yearning for movement, seems quite at home with both his environment and situation.

We run out of the hills the next day and on to the plain that runs right up to the Zambezi and the Kariba Dam. Motorcycling in Zimbabwe is pure enjoyment. We stay in Harare in a campsite that is far too large and open to thefts some three miles from the city centre. We go into the city that evening and again next morning before driving out to Kariba. Harare is a blend of the old colonial buildings, two storeys high and ornate facades and new modern office blocks. These two elements seem to be in harmony and contrast strongly with Nairobi where such differences highlight the divisions between the rich white people and poorer Asian and Black people.

Harare and the Kariba Dam

In Harare we change the bikes’ oil in a busy Mobil garage and manage to exchange one of our inner tubes for a brand-new Zimbabwe-made Dunlop universal tyre. The bike shop owner explains that there are such tight foreign exchange restrictions that any bike parts have to be imported and are in very short supply. We leave the city about lunchtime and almost without noticing knock off the 250 miles to Kariba. The miles seem so easy now and the bikes are going as well as ever. We never think of them any more as potential sources of trouble. When we meet people, we like to say how old they are and how unsuitable they are for the trip. Previously we had played down such things, worried that serious overlanders would think that we were just the sort of folk who came ill-prepared and who would end up needing to be rescued. Now we’re typically English battling on with the odds stacked against us ill-equipped except for rugged determination.

That afternoon as we roll on through the last of Zimbabwe we stop for lunch at the Chingi Caves with its azure pools of still water hundreds of feet below. We later drive through the Great Dyke, a thirty-mile-wide trench which gashes its way north-south across the otherwise flat plain. We stay the night at Kariba and next day cross the dam wall into Zambia.

Through Zambia to Malawi

We trail the hundred miles to Lusaka a journey which takes all afternoon. This is much more like the real thing with roadblocks, diversions and broken-down lorries. Now we are driving in Africa again. We camp at the Andrews Motel and transit the 400 miles to Lilongwe in Malawi inside two days. On the first morning out of Lusaka we are amazed and delighted to see the bright blue truck of the overland group that we spent time with in Zaire. We leap off the bikes and all jabber away for half an hour before going our separate ways. Once again Zambia does not receive much copy for our three days there. We had absolutely no problems, people were friendly to us without exception and no one took us for spies. There just did not seem to be a lot to stop for.

Malawi and the Nyika Plateau

We always knew that Malawi would be a confusing place. Everyone we had met had liked and praised it. We were both uneasy before we entered and unconvinced by the time we left. We stay one night in Lilongwe and head west to the resort of Salima Bay on Lake Malawi. There we find a campsite sandwiched between a fishing village and an opulent hotel incongruously surrounded by a chain wire fence. We head off into the local village and buy chaamba, fish from the lake, delivered only minutes before from wooden boats returning with the day’s catch. It a breezy evening with a gusting wind blowing warm off the lake.

As usual on Africa’s best nights there is a full moon. As the fish are gutted, we sit on the sand listening to the low murmur from the village and gazing at the moon’s reflection as it plays on the waves. We cook the fish with rice and eat in silence unable to speak in such an overpowering atmosphere. Later we move into the hotel and come across a party of hunting and fishing Africaaners who have just hit town. We flee to some chairs by the lake shore and drink our beer in peace. Later we drag our sleeping bags down to the shore and fall asleep to the lapping of the lake’s small waves and the rush of the constant wind. Dawn and sunrise over the lake occurs in a series of six-time lapse stills as I wake up, struggle to stay awake and fall asleep again for short periods.

Today the process of packing up takes forever as the peace and calm of the lake has sucked out all of our energies. Eventually we reach the main road and strike north. Malawi is meant to benefit economically from its South African links but has very little in the shops. Farther north it becomes hillier and cloud builds up over the mountains to the north. By noon it is cold enough for us to have put on most of our warmest clothing and all afternoon it seems about to rain. That night we camp in the grounds of the rest house at Rumphi at the foot of the Nyika plateau, the setting for Laurens van der Post’s eerie Venture to the Interior. Our decision to go to the top of the plateau is clinched by an offer by fellow resthouse dwellers, the Hindes, for us to stay in the cabin they have rented there.

The track up to the top becomes difficult after the Park Gate with long stretches of fine red, soft and powery “bulldust” sand that is made more slippery by the drizzle that has by now started. The country at the top is very to the Scottish Lowlands with hills rolling gently off to a far distant horizon. The sight of zebra close by brings us both sharply to a halt and breaks us out of our daydreams. We switch off the bikes and stare silently until the animals canter off across through the tall grass and are out of sight.

That night we stay in the cabin. The couple are in their late fifies and have been in Malawi since 1964. Formerly in India, Mr Hinde is now a tea estate manager for Lonrho near Blantyre in the south. Mrs Hinde is a headmistress in Limbe. They are ambivalent about the government of Dr Banda which they admit is ruthless and autocratic but which has maintained stability for over twenty years in what they feel is a violent and changeable part of the world. Living standards are, however, as low in Malawi as in any place we have visited and with a basic minimum wage of only 77 tambala (20 pence) per day it seems to be in the multinationals’ interests to keep things very much as they now are. We remain amazed that people in Malawi remain as friendly and well-disposed to white tourists as they do. After a protracted breakfast and a session packing the bikes very slowly, we say heartfelt goodbyes and leave. It is a hard slog off the plateau and after the enjoyment of the last two days we find ourselves suddenly in bad moods. The day remains heavy and humid and adds to our lack of comfort. By the time we arrive in Livingstonia in the far north we are both fit to drop. Even though we had ridden up a boulder strewn track for some 15 miles to reach the top of the escarpment we glance around the village very quickly only really stopping to listen to three girls singing a cappella on the village green. It may sound strange to say village green but the whole place has been set out along the lines of a Scottish mining village with two rows of semi – detached cottages running along the main street. It all looks very incongruous surrounded by tall broad-leafed trees and with the deep red dust of Africa. We drop back down to lake level and camp the night in the bush both tired out.

We drive through a misty dawn along the lake shore heading north. The sun plays hide and seek through the thinning cloud until we are well past the lake. We cross out of Malawi but are held up at the Tanzanian customs while they fetch a special form for my carnet-less bike.

Tanzania

Leigh says he’ll see me back in London if they don’t let me in. Solidarity in adversity. They allow me in without having to lodge a bond for the bike. We flee before they change their minds and drive through to Mbeya through dishevelled mountain towns strewn with fruit and vegetable remains. In one town we see a very old British bike pounding its way through the streets and cannot believe that such a bike has been kept going all these years. We look appalling when we arrive in Mbeya but are allowed into a hotel to change money and are treated like the most important of guests as we take afternoon coffee and sandwiches. By nightfall we are halfway to Iringa. Whenever Leigh has had enough of camping he tends to restate his belief that we are in lion country which convinces us to pass the night in the nearest hotel. The one we choose has been signposted for a few miles in the town of N’gawa. Washing is from a tap in a courtyard surrounded by the other tiny rooms. When the bar closes at 2am I finally manage to get to sleep.

We are up and off before sun up. It is a cold blustery morning and we plan to do 140 miles before breakfast in Iringa. The first 70 miles seem to take forever. The clouds roll off the Highlands and a misty drizzle starts. We put on more clothes to warm up. The sun does not reappear until Iringa. For the umpteenth time we lose an oil container off the back. Unusually this one had some oil in!

We last came through Iringa on a sleepy Saturday afternoon. This time the town is alive and busier than anywhere else so far in Tanzania. Somehow, we avoid an early death on the steep hill up to the town and after a meal we head out east. Twenty miles out of the town we drop a thousand feet off the plateau and within ten miles the temperature has risen ten degrees. We are now back to T-shirts and jackets. The road passes along the southern tip of the Masai Steppe and we see the brightly adorned Masai for the first time. Both men and women have red tinted skin and wear bright red smocks or dresses reaching to their knees. Often their hair is dyed red too. The men are relatively tall for Africa and their earlobes are enlarged to permit huge earrings to be carried. Both men and women wear numerous bangles and necklaces and the men bear thin spears to protect the cattle.

We now pass through a baobab forest some thirty miles wide and later on in the afternoon the main road to Morogoro enters the Mikumi Game Park. With the park being on the main road we do not expect to see many animals but almost immediately are amazed by the variety of the game that is visible. Within five miles of the entrance, we have seen elephants, Thomson gazelle, warthog, zebra, buffalo and giraffe. We stop and watch the giraffe forage as they munch at the higher leaves. They are much taller than we had expected with brown square splodges on their coats surrounded by light brown lines. They move quickly and gracefully. Later we think that we see a rhino in the distance – we hope we did as we never see another during our trips around the game parks of Kenya.

We stop in Morogoro and camp in the grounds of an Italian restaurant. The owner Mama Perina has a son who is travelling and she hopes others will let him stay just as she is letting us. Next morning we face the long-dreaded main road from Dar Es Salaam to Kenya, a run down, potholed and disintegrated stretch lasting some 200 miles and destined to be awful most of the way. We are now under 500 feet above sea level and the land around is very lush especially when compared with the burned-up landscape of yesterday. The main crop is sisal with its thick splayed leaves and central stems reaching up to four feet high. Towards the end of the day, we begin to rise into the range of hills that continues as far as Mt. Kilimanjaro farther north. To our left the Masai steppe falls away to infinity – the horizon occasionally broken up with hills. There are few people or vehicles around. The Masai remain on the steppe free to graze their herds away from the sisal plantations and the other permanent farms.

We pull off into a tiny hotel just before dusk and eat in one of the minute restaurants in the village centre. There are a number of big trucks parked up nearby whose drivers are eating there too. There are half a dozen tables each surrounded by four rickety chairs. The place is lit by a couple of gas-powered lamps and there is a tap and washing basin in one corner. We have our usual combination of samosa, omelette and chapati. We walk back to the hotel in the warm night air. There are small lights on in the houses that border the road but the village is almost without sound. This and the cavernous starlit sky add to the sense of vastness. Across the plain the far hills are an immense silhouette which provides a backdrop for the few cars that are still out.

Next morning is clear, cold and beautiful. Before breakfast we have a long section of sudden braking and pothole dodging interspersed with bouts of singing Zambezi, Tom Hark and other perennials from the trip. These performances are capped with dive bombing runs on each other across the full width of the road driving on the right and Leigh’s piece de resistance, standing up on petrol tank and shouting, “Look! No hands!”. For some reason biking in Tanzania is the most fun of the trip. Perhaps this was because every inch of asphalt is an unexpected reward for some kindness we suspected we have never done.

Mt. Kilimanjaro

Halfway through the morning we notice a white cloud that does not seem to move very much. We stop and stare for some time before agreeing this must be Mt. Kilimanjaro. Its base is still some thirty miles away but already it towers above everything. The flat peak is snow-capped and juts out through the cloud layer three-quarters of the way up. The base of the triangle is covered with dark green vegetation. The day stays cloudy as we approach Moshi and this remains our best view of the mountain. Moshi is a bright, clean, busy town where we stop for our last Tanzanian money change and the inevitable celebratory coffee. The road running west to Arusha passes first to the south of Mt. Kilimanjaro and then Mount Meru. After we find a pleasant campsite by a lake we head into Arusha. It is a grubby town with ornate but run down streets and buildings. It holds an air of mystery as if plots are being hatched far from the tourists’ gaze. The shops are full of zebra skins and tourists. The latter are a rare breed in Tanzania but Arusha is the gateway to the Serengeti. We still feel they have no right to intrude on our version of Africa until Kenya.

In Gaborone we had read The Road To London by Eric Attwell who travelled to Britain from Port Elizabeth in South Africa in the late 1930s with his brother Jack on two bicycles. The author had written of a hotel which had claimed to be exactly half way between Cairo and Cape Town. When we find the hotel, it no longer has the plaque with this claim but it still stands and beside it is a roundabout which has signs giving the incorrect distances and pointing in the wrong directions to over thirty places including Cape Town and Cairo. Interest in Arusha satisfied we settled down to more coffee. That night’s meal at the camp is delayed by the demise of our eccentric petrol cooker that has taxed Leigh’s ingenuity since Morocco.

Next morning we cut it far too fine with our last shillings in a petrol station but feel invincible as we set out for Nairobi. Around Arusha and Mount Meru it is cold and the thick cloud persists. The Masai heading into the town by foot or crammed in the back of pick-ups all wear their cloaks tightly wrapped around them. We gain height and suddenly reach the top of the range of hills and Africa spreads out before us sunshine and all. The moment focuses everything I had expected East Africa to be into one moment. The rolling plains, towering mountains of huge white cloud, a large herd of cattle tended by a single boy far off on the plain and a long high plume of dust where a pick-up heads off to a distant village. Later we fall down on to the plain below which shimmers with heat and we make our way slowly across it towards our last border crossing. We are both very excited as we leave Tanzania and are only barely able to keep our elation under control as we get through Kenyan immigration.

Kenya

These customs will be tough and I take a number of sincere pills as I recount the tale of the carnet and proffer the dog-eared statement I made to the police in Gaborone. The official gives me ten days in which to get the bike out of the country. This should be enough and we babble our thanks. As we begin the hundred miles to Nairobi, we can scarcely believe that we have got to Kenya.

We trundle north quite slowly and stop for a while to look at an ostrich that leaps out behind us across the road. We arrive in Nairobi by mid-afternoon. The centre is visible from the airport ten miles away and appears as a mass of concrete office blocks. We change money and head into the suburbs to a campsite in the grounds of a house. This seems to be where all the overlanders are stopped either at the end of their journey or halfway south. We chat to a few but their elation to be here died days or even weeks ago. After dark we troop into the city centre for the large curry that we first promised ourselves four months before. We walk back most of the way even though we are convinced that this is one of the areas that people told us to avoid after dark.

Next day we try to be businessmen in Nairobi. First thing we sign up for a six-day safari beginning tomorrow. The rest of the day we stagger round Nairobi learning about air freight, crates, cubic metres, volumetricity and Air Sudan.

On safari

Our six-day safari begins on a truck at the mercy of Joseph, our hilariously misanthropic Kikuyu driver. First stop is at the top of the escarpment where the plateau halts awhile to let the Rift Valley pass south. For Leigh and I the view is only half the story. For us to have made it this far to see it is the other. We toil on all day halting the night at Lake Baringa home of hippos, crocodile, fish eagles and a gigantic ponderous tortoise some two feet high. That evening a few of us go to the bar where the whole of the local village is congregated drinking chibuku and Tusker beer bottled in Nairobi. We stumble back to the camp in a night so pitch black that it is impossible to see even the side of the road. The following day it’s flamingos on Lake Nakuru and down to the Masai Mara Game Park via Narok. We spend three days there and see a large number of white tourist combis migrating over the plains, $200 a go balloon rides and a limited number of wild animals. The Masai Mara is absolutely littered with tourists making the place feel like a gigantic zoo rather than a natural habitat. We do see cheetah and lion but I preferred to see the giraffe, ostrich and warthog. Strangely the game drives did not concentrate on these less spectacular species. Most amazing is the sight of a wildebeest migration with a column miles long with each animal following the exact footprint of one preceding. The wildebeest column seems to be thrown into confusion by any obstacle or variation in the line of march.

After the safari we spend another day trying to find an escape route for ourselves and the bikes. Walking along a street in Nairobi, we meet Andy who we had last seen in Victoria Falls, and he tells us about his two friends who are trying to sell air tickets from Nairobi to Frankfurt. A highly dubious deal is struck. We will meet again on the 25th, they will check us on to the plane and we will fly off. For some reason beyond logic and without discussion we decide to sea-freight the bikes back from Mombasa and set off for the coast next day.

To Mombasa and the Indian Ocean

We carry our first passenger on the trip down to Mombasa. Conrad is an English guy we met on the safari who is on a round the world trip with limited funds and tastes that do not match these limits. The bikes are very overloaded. We feel that Conrad who is sporting shades and no helmet will be safer if he rides with Leigh. My bike acts as the dromedary. We set off so late that morning that we get only as far as Voi by late afternoon.

We find a hotel where we all share a room for £1.30. That evening in the hotel’s bar I chat to the owner who tells highly improbable stories of his career. He used to own a large curio-shop in Arusha selling ivory, skins and general tourist items. He numbered amongst his customers Aristotle Onassis who one day bought up half the shop. This business lasted the until the mid-seventies when there was an almighty row over Kenyan domination of the Tanzanian tourist trade. All the Kenyans’ property was confiscated and they were forced to leave. From Tanzania he went to Kampala where he set up a nightclub and a hotel. Once again, the Kenyans fell foul of the government and he was elected spokesperson of the Kenyans to discuss the situation with none other than Idi Amin himself. He said that things got dangerous after that and he had to leave hastily with all his money in his car and flee back to Kenya. Amin, however, was okay he said but his problem was that his advisors all told him different things that were in their own interests. This thoroughly confused him and it was because of that that he behaved so erratically. Now his only venture is this small roadside hotel but he has heard that the government in Tanzania was opening things up again so he might go back to Arusha.

Journey’s End

The next day is our last biking in Africa. We dawdle along at a pace and soon stop for a protracted breakfast of omelette and chapati washed down with numerous cups of tea. The roads are deserted and we drive two abreast for long stretches Easy Rider style with Conrad our unlikely Jack Nicholson. Around lunchtime we come to the city outskirts and pose for photographs by a Welcome to Mombasa sign.

In ragged formation we drive into the town unconvinced of what to do next. There are lots of chores still to be done in getting the bikes shipped back.

We realise that the trip is over and we are devoid of any energy to get our tasks done at least for now. We’ve covered over 16,000 miles on our little bikes and seen the places which we had only dreamed about six months before. Working out what comes next will have to wait as the Indian Ocean sparkled and beckoned from the bottom of the street.