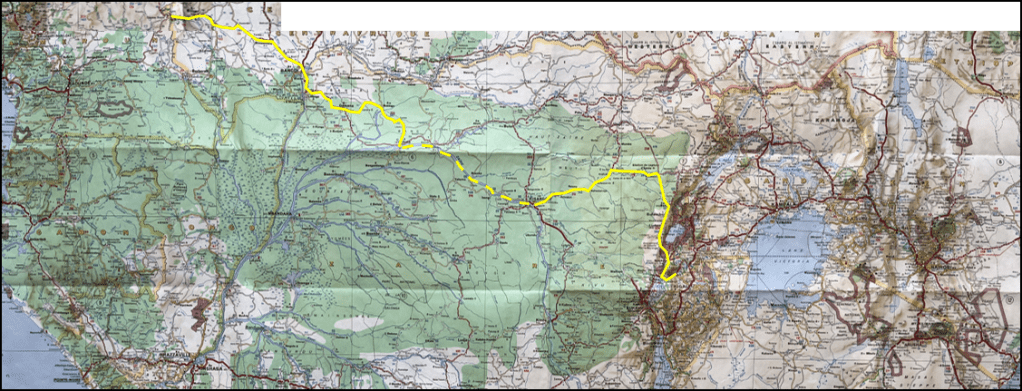

Route map

Central African Republic

We ride all day through the rain forest. There is not an inch of this main track that does not have huts and villages crowding along it. The road is pretty awful with corrugations, ruts and much standing water. By evening we have seen nowhere we can just pull off so Leigh suggests that we go to a roadside bar and ask if we can stay. This we do and meet some of the friendliest people during our time in Cameroun. The bar is run by a woman but owned by an old man who we chat with in French throughout the evening. About 10pm everyone who has been drinking there gives up and we sleep on the floor of the bar. During the night there is a spectacular storm that leaves the piste awash next morning but we remain gratefully dry. About 100 metres from the bar we find a German Combi parked up, the owner of which we have already met in Yaounde. After an hour or so the Combi passes us and stops and we all agree to meet up in Bertoua for breakfast.

Peter is an East German who succeeded at the second attempt to escape to the west via Yugoslavia and who now lives in West Germany. We travel with the Combi as far as Bangui.

Peter is losing oil fast and goes through 50 litres in just 600 miles. Although our problems remain with our stomachs which are by now completely in revolt, we are helped no end by Peter who is an excellent traveller and is worried by nothing and just happy not to be working for a living at this precise time. We are delayed at the Cameroun border exit as Peter drives through without stopping and is ordered to stay until the next day. Perhaps because of his past experiences he despises all in a position of authority and treats every official with indifference which is never the best way in Africa. We remain at the border, have breakfast and as we seem unconcerned by the delay they let us go aound lunchtime. At the Central African Republic border at 4pm we are told that we must pay $15 for processing the carnets during overtime.

The C.A.R. appears little different to Cameroun. The people are friendly outside the towns, the officials stop you and insist on cadeaux (gifts) before you can continue and then let you carry on when you say no. The gravel roads are, however, superb and we are able to hack along at 40mph.

Of all the countries we visit the C.A.R. is still the most overtly possessed by the French. Bangui, the capital, has its own immigration post 12kms before the city centre to prevent the rest of the country’s population swamping the relatively rich city where the white expatriots are housed. An amazing sight even before you reach Bangui is to find an army base guarded by French soldiers and a long column of armoured vehicles driven by them. In the capital your visa has to be confirmed. This requires a visit to the “Centre de Securite National” a fortress high on a hill commanding the town which is a hive of military activity. The Presidential Security Service is most in evidence here sporting their dark brown uniforms and black panther insignia. We go up into the camp to collect our passports and spot Central African Republic soldiers being trained by these latter-day foreign legionnaires. French interests and their raw material requirements ensure a continued presence in West and Central Africa. They keep the army strong and a ruling elite powerful and it makes little difference if the map itself is no longer coloured purple.

Zaire – to Lisala the Zaire River

The trip into Zaire is swift and efficient. A new ferry takes us across the wide and placid Ubangui river and deposits us at Zongo.

Most overlanders head further east and cross at Mobaye on their way to Lisala on the Zaire river. Our route may be harder but appears to be 200 miles shorter. Apart from an outrageous Taxe de Ville we emerge from Zongo unscathed. Mocking us as we leave the town is a long closed down building still proudly bearing the word “Hypermarche”. It is 150 miles to Gemena and the first chance to change money and buy food in Zaire. We know that Zaire will be the biggest physical challenge of our trip after the desert. Our first afternoon is O.K. and the roads are no worse than they were in the Cameroun. We camp the night in one of the road maintenance gravel pits which are destined to be our hotel on a number of occasions in Zaire. The vegetation is lush with tall, thick grasses all around.

It is still not quite what we imagine the jungle to be and is at most dense green savannah. The stars are the brightest we have yet seen and shame even those of the desert. There is a spectacular sunset and the next morning the sky is on fire with the high cloud a searing crimson.

The track to Gemena passes through long, linear villages bordering the road. The men are invariably at rest or sitting around talking. The children, meanwhile, tend the animals and the women carry great loads on their heads or on their backs with leather straps around their foreheads to support the weight. We arrive in Gemena but the bank is already shut until the next day. They allow us to change our travellers’ cheques and in return for a cadeau of a long-expired calculator that we had originally planned to sell. Leigh goes foraging in the town centre and comes back with a pack of spaghetti and a tin of fruit from South Africa. We laugh at the irony of buying tinned fruit when the only things available in the markets are pineapple and banana. We learn that the ferry south at Akula is out because the river is too low so we must head east to the main track between Mobaye and Lisala.

There now follows the worst afternoon of the whole trip to date when the sandy track turns to quicksand after a downpour. We slip, slide and fall over continually.

People just stare at us as we pass by them more often than not horizontally. We stop for the night in a gravel pit. Leigh‘s stomach has by now given up the ghost and he collapses into his tent without eating. I eat and then read for a while before bed. We struggle into Businga the next day to buy some bread.

The road south is a sea of mud. The potholes often contain water a couple of feet deep and straddle the width of the road. We are frequently compelled to take to the jungle next to the road that has been beaten down by the trucks that are forced off it from the depth of the water. Trucks come along lurching and swaying massively overloaded with numerous passengers clinging on to the sides and lying flat on the tarpaulins that somehow hold their loads down. These old Fiats and Mercedes are often seen broken down with a gearbox in pieces or their rear end precariously held up on blocks as an axle is replaced. If spares are being fetched from afar a guard is left behind to look after the precious loads. We ride through thick clumps of bamboo which provide dark canopies that block out most of the light. The forest is now so dense that it is impossible to walk into it and everyone we pass carries a panga. The road and air are full of butterflies of white, yellow, red and blue although we never catch sight of the famous Papillon.

We are astounded to meet an American couple on two mountain bikes who have come down through Egypt and Sudan. We feel pathetic in such company and although they are in good shape they yearn to reach East Africa. Sometime in mid-afternoon we arrive in Lisala, the home of the famous 1974 boxing match The Rumble in the Jungle “in Zaire, in Zaire”. It is a spacious town covering a large area with wide streets and colonial houses set in individual plots with large gardens. All the buildings are in bad repair. We reach the dilapidated Hotel Centquinnaire which was the Hotel de Ville in earlier times and which is set at the top of the long slope running down to the river Zaire itself.

A journey up the Zaire River

There is an overland party camped there and we jabber on to them like men possessed. We sit there dazed after the struggle of the past few days and talk for a long time. They are a friendly mixture of Australians, New Zealanders, Brits and Americans who are waiting for a river vessel to Kisangani in the East. Every night (and even during the day) stuff is being stolen from their camp and they are mounting their own guards now. I wander into town that evening and meet an older man who takes me to the market and the restaurant.

By night all the stalls are lit by small gaslights and the market even at this late hour is quite busy. Here supplies of soap, cigarettes, matches, milk powder, tomato paste and fruit are plentiful. All the food stores sell these items and virtually nothing else. We find the only place in town serving food. I buy my own lump of bread from another stall and bring it back to my table. The older man tells me that until he retired some five years before he had worked in the civil service both here and in Kisangani. He had been in the education service both before and after Independence. He says that he was educated and trained by the Belgians and says that both the government and education had been well run. Lisala had once been a major port on the river but had declined greatly in importance in recent years and large parts of the town were returning to the jungle. In addition, there was far less traffic moving up and down the river now.

During the next few days we rest and try to organise a boat. One afternoon a dozen or so of us play a riotous game of baseball on a nearby building site watched by a couple of hundred amazed locals. That evening a German guy working in a logging operation in the jungle comes into town and talks about the difficulties that he has keeping it going. There are three elements to the operation – a Caterpillar vehicle to drag the logs to the mill, the mill itself and a lorry to transport the cut timber. All of these run on diesel but between them he only has one set of injectors. Only one operation is possible at a time and he swaps over the injectors depending on which piece of plant he most needs that day.

On the last evening, we were there all hell breaks loose when a boy is caught stealing from a tent. Almost immediately a large crowd gathered and a guy from New Zealand who has had $800 along with all his documentation and valuables stolen previous day is laying into him trying to find out where his own stuff is. By now everyone is kicking and beating the boy who is tied up with rope. He is struggling violently but not about to tell anyone anything. This goes on for some time and no one has much idea of what to do.

The locals are still beating him with sticks in order to find out what he has taken or so they say. In reality it seems like it is a good excuse to beat someone up. Sid who is the driver of the overlanders’ truck and I are afraid they are going to lynch the boy and so we decide to take him to the police before this can happen. We take him the 500 metres down the road to the cells pursued by the mob some of whom keep running up, kicking him and beating him with their sticks. We hand him over to the police who assure us that he will be dealt with leaving us unsure whether he might not be better off with the mob. Those from the group who have gone in with him say that the police seem about to kill him there and then but it does not turn out quite like that. The next morning, we find out that he has escaped and disappeared. The locals are furious with us and insist that we should have left them to deal with things their way. They say that the police are corrupt and have been bought by him using some or all of the money that he had previously taken. I think they are probably right but it is hard to witness someone being beaten senseless for stealing. When in Rome, however…

Once we find a cargo boat headed east to Kisangani we have an hour to pack before it casts off. We load the bikes and the rest of the stuff and begin to settle down to a long journey on this most awe-inspiring river. The river at Lisala is some 3 kms wide with large clumps of vegetation floating towards the coast 500 miles farther downstream. We set off and make rapid progress with the boat still on its own and not as yet pushing any other barges. The vessel is powered by two enormous and loud supercharged two stroke diesel motors known by Sid more technically as “Screaming Jimmies” made by General Motors in Detroit.

After an hour or so a small wooden boat (known locally as a pirogue) slips from the southern bank carrying a short white man who gets on board. This is Dimitri the ship’s owner who has been hunting in the forest for a couple of days. Dimitri is a kind and generous man who allows us all free run of the ship and returns our fares that, he says, the captain had had no right to charge in the first place. He is, however, a terrible shot and a lousy successor to the great white hunters of yore missing all but one of the creatures which we frequently slowed down for him to try to bag.

That afternoon we pick up a 150MT barge of cocoa oil and a broken-down boat that is lashed on to the port side. We halt the night at Bumba and after “immigration” next morning we are allowed to wander around another remarkably decaying port and town. Later we pick up another barge from a large factory at Lokutu containing this time 300MT of the oil and guarded by an armed soldier.

Pirogues constantly detach themselves from the isolated villages along the river banks and tie up alongside our vessel sometimes up to three deep on either. On occasion these long and slender dug outs do not make it and capsize in the ship’s wake.

The ones that are successful sell fruit, chickens, eggs, monkey meat and various kinds of fish. By the morning of our fifth and last day on the vessel the river is only about 1km wide. It is still fast flowing although its immense size makes it seem slower. The forest along the way seems impenetrable but we know that there are numerous paths running through it between the little villages we have seen.

At night when we stop it is very quiet and we can feel the fabled brooding intensity of the river.

During our time on the boat there is little to do apart from watching the forest go by, reading and talking to the other travellers. Every night darkness comes quickly and is accompanied by intense crimsons and deep shadows etched against the black river. Often as you look back into the fading light the only life on the river is a lone pirogue heading for the shore and the comfort of a nearby village.

Kisangani and East Zaire

We are as far into Africa as we can get. This really is the centre of the jungle as we approached Kisangani, formerly known as Stanleyville, and at the very Heart of Darkness. Stanleyville had been a key administrative centre for the Belgian Congo and the focus for trade along the river to the west coast and the Atlantic Ocean. It had had large hotels, numerous machinery and car dealers and civil service headquarters. Almost overnight the Belgians had cut and run leaving behind no local administration or continuity. What remains are the shells of that earlier era. Colonial and art-deco buildings apparently with few occupants, unused patrol stations, closed down bakeries.

The colonials have gone but life goes on as ever albeit in the incongruous theatre set of Stanleyville. As well as the locals, there are small Chinese and Greek communities. The Greeks still have their own restaurant and church but their numbers continue to dwindle. Dimitri and his family were about to leave and go and live in Kinshasa.

Six of us go out for a morning at the Stanley Falls. Africa rarely gives up her secrets without a struggle and this morning will be no exception. On the way to the Falls, we pass an abandoned and derelict mosque.

We discover that this was built during a short flirtation with Islam by President Mobutu who saw the Arabs as a good source of aid. When this ceased Catholicism again reigned supreme.

We reach the Falls and are immediately given the rates for photography and for a pirogue out to see a display of river fishing techniques.

Surreptitious photos are taken, two of the group are detained. One of these is Arlette — a whirlwind figure of 4ft 10inches from Australia. Two guys threaten her for having taken the photos. Eventually we all agree to pay up and we are accompanied by twenty locals to see the fishing display. We all retire reasonably unbowed to the ice-cream parlour. This visit causes my stomach’s final surrender and the purchase of some more antibiotic flagyl. With great reluctance we pack up to go, leaving behind the Overlanders that we have been with for over a week and who have showed two knackered bikers enormous kindness. The tour’s nominal guide Tony has insisted that we do not stop at Nairobi as East Africa is the good bit and don’t forget to see the gorillas which are the best part of Zaire. I just need to put some weight back on.

Just as we leave, I hear a Velvet Underground song coming from a Land Cruiser. Jubilant I go over and thank the guy who looks at me as if I’m nuts.

Eastern Zaire

We travel along the only asphalt we find in over 1,000 miles riding in Zaire – all 13 miles of it and set off for Epulu home of the Okapi some 350 miles due east of Kisangani. The rain forest begins to thin. Later that day we see Pygmies for the first time. We camp that night in a trusty gravel pit already over half way to Epulu. Leigh spooks us both this evening announcing that he does not feel too safe here. I thank him and spend three hours staying up and reading. He, clearly worried sick, settles down immediately for a long and uninterrupted sleep. The next day I suffer from having taken excess chloroquin tablets further to guard against malaria. They affect my vision causing me to off three times during the day. The last time it happens we are only eight miles from Epulu and as the bike keels over it hits a rock and bends the gear lever. “Be careful you don’t kick it straight, Jez, or the whole thing may crack off.” suggests Leigh.

“Oh, it’ll be O.K.” I insist. It is not of course as I give it a hefty kick. We are in the middle of nowhere with a totally unusable gear lever. I shove it into second and drive slowly to the town. As we arrive, I fall off again and manage to snap the brake lever off. I don’t deserve it but at this point we get a very lucky break. Across the road from the camp is a welding shop. It’s not quite as simple as all that because the shop owner has no welding rods of his own although he has the gear. He informs us that the owner of the camp should have some welding rods spare. An arrangement is reached and a new gear lever gets made. That night we spend in camp with a Guerba overland truck. These guys are roughing it in style and have a campmaster to supervise the cooking so much so that they have banana fritters for dessert than a few old biscuits as most groups seem to. We have heard lots of stories about bridges being down in Eastern Zaire and bog holes that swallow trucks and we leave Epulu bent on self-destruction spanning rivers and drowning in mud. To avoid the bridge problem, we turn south at Mambasa down a barely known jungle track some 80 miles long. The track is an absolute mess now because of the recent rains and the fact that the big trucks have had to use it as they are unable to get through further east. There is churned up mud everywhere.

After an hour or so we stop and chat to a local who informs us that there are only twenty big bog holes left before the bridge over the River Ituri and easier times. Presently the we come across the tyre marks of a large bike and then catch up with an exceptionally overloaded BMW belonging to two Germans Alfred and Doris.

For once we find some people having a harder time than us. The BMW is leaking oil and Alfred is scared to hammer the traditionally weak clutch on the big twin. We travel with them and spend the rest of the day carrying their stuff and pushing the bike through the mud. Doris is part human, part JCB as she carries 35kg bags across the bogholes, lifts the whole of the rear end of the bike up and also pushes the thing out of the mud. Alfred, only some 5ft 6 inches tall, somehow manages to guide the lumpen mass of bike through the morass. There are stretches of water over a hundred yards long in places lying across the whole of the width of the track and great ruts full of mud and water where lorries have become stuck and have been laboriously dug out. We reach the river just before dark but not before I have managed to fall off whilst waving to some people as we are passing. We camp the night in an abandoned village close to the bridge and all go to sleep very early absolutely exhausted.

Next morning the road is just a difficult as before. We climb into the mountains and enter the coffee growing area which lies below the Ruwenzori Mountains.

In Beni we stop and go for a meal of omelette and salad. We find plenty of food including enormous round cheeses which are delicious. Bread is plentiful. We meet two overland trucks that have just spent six days coming down the jungle track – one day they managed one mile all day.

They are exultant at having got through and talk only slightly less than us. Zaire is beginning to get a bit easier. Next day we cross the equator high in the mountains on a diversion from another broken down bridge.

To celebrate we eat some Cadbury’s chocolate we bought in Butembo and which is made in Nairobi. We are now even more convinced that we will like Kenya!

We know that we are now close to the series of bogholes that we have heard stories about ever since we got into Zaire. Bogholes are caused by lorries’ wheels spinning and churning away more and more of the road. One is so deep that our heads are below the normal road level as we ride through.

Although they are dry and relatively easy for us to pass through there are numerous cars and trucks either stuck or waiting their turn to go through.

The land around is very fertile with dairying as well as cash crops. We buy an enormous punnet of strawberries along the way. The next day we reach the Virunga National Park and descend the Kabasha escarpment with flat savannah plains to the south and Lake George to the east.

Suddenly we are in East Africa driving through burned and yellowing tall grasses. We see a herd of antelope to our right. At the Park Lodge there are baboons. We cross a stream and Leigh spots hippopotami wallowing in the water below. Even at a distance they appear enormous and bloated and when they open their mouths an enormous mangled pink mass is revealed.

The remaining miles through the park are dreadful. Fresh earth has been laid down on the track but has not yet been rolled flat and is even harder to ride through than deep sand.

Outside Rutshuru there is a rare roadblock. The officials there demand to see our insurance for Zaire. Leigh gives a Norwich Union policy whilst I give them a renewal slip. They have served us well so far but cut little ice here. We argue for half an hour before both parties retire into respective huddles. For our part we are not about to shell out £40 with only 20 miles left and over 1,000 miles of Zaire behind already behind already us. Later we simply ask the soldiers to let us go. They would but we have offended le patron d’assurance. This will take a major bout of grovelling in French to sort out. Le patron loves every moment of my miserable performance. We are allowed to proceed with honours reasonably even.

Goma and Gorillas in the Virunga National Park

Most of the last 20 miles to Goma are done in the pitch black over sharp and slippery basalt rocks. I follow Leigh closely as my headlamp is not working.

Goma slowly appears in the distance and we reach it an hour later. We find the Cercle Sportif campground and are overjoyed to find that the steak, chips and salad on offer is available. Goma is an old colonial town and has the bonus of a wonderful bakery. Good bread and cheese lift our spirits and we get provisions prior to our trek to see the gorillas. Leigh goes to the tourist office and signs away $80 and is told that we must be at Rumangabo that evening to see them the next day. All we know is that you walk in the late afternoon up into the hills for some four hours, stay in a hut and next morning set out for another hour or so’s climb into where the gorillas live. Nearly every one we have met says that this is a highlight of the trip especially as there are so few mountain dwelling gorillas left on earth.

We cannot face taking the bikes back down the track so arrange to catch a bus leaving at noon. This leaves at 1.30pm already full with 20 people on board. By 2pm we are out of Goma with at least 35 passengers and more packages constantly being thrust through the windows. We pass a village market, stop and a furious round of shopping begins. The inside of the bus now resembles a greenhouse and the driver continuously shifts his own vegetation to catch a glimpse of the road.

We arrive at the turnoff and by 5pm reach the base camp. We have arrived too late to be taken up to the mountain hut tonight and so must wait till morning. We know that tomorrow will be bad enough without a four hour walk first thing. Eventually to shut us up a guide is sent to take us up. It is almost dark when we meet four Zombie like Danes staggering back to the camp after doing the whole visit in one day. It starts to rain and we slip and fall over continuously. Later a full moon peeks out and illuminates the path.

It is eerily quiet as we climb through a string of villages on our way to the hut. Every inch of earth is cultivated. Our guide stops to talk to friends in every village. We dare not stop in case our legs never move again. We finally reach the hut and there are great views now that we are so high up. There are lights a long way off and a dull green glow covers the jungle. Mountains and extinct volcanos are clearly etched against the stars. As always in Africa the effort is rewarded.

Next morning we are up at dawn and ready to roll. Our guides arrive at 9am. We set off for the hills.

After an hour or so we enter the forest and walk a clearly marked path until we reach a hill. Progress then becomes very slow. We slip continuously and we sense that the guides have no idea where we are. There is by now no track to speak of and the guides force a way through the forest with their pangas. Some three hours after leaving the hut we are finally a place where gorillas have been recently. The surrounding vegetation has been beaten down and their strong cow like excrement lies all around. We walk over an ant hill and are attacked by hundreds of killer ants. These get all over our clothes and bite viciously. They have to picked off one by one.

We finally catch sight of the gorillas which the guards have somehow located. They are happily munching leaves, branches and grass in the undergrowth. This is a group of females and their babies. The babies can climb higher in the trees than their mothers who frequently crash to the ground as trees give way under their weight. The females are about five feet tall, black, hairy and stout. They lurch ponderously as though even the effort of moving to new food is quite uncalled for. We remain some distance from this group as our guides say that the only time that the gorillas will turn nasty is with their young around.

Later we find two males and can go right up to them. They are quite unconcerned at our presence and munch away continuously. We also see the family elder – a silver backed male who is enormous – and at least six feet tall. The climb and the search has all been incredibly worthwhile. We have never seen such animals in their natural habitat before and we stand and just gaze at them for many minutes. Eventually our guides motion us to leave and we begin the long trek back to the road.

We get there just after dark and manage to hitch a ride back into Goma. This Mazda pick-up is so overloaded that we can only just cling on to the top of the enormous load of sacks and vegetables which it carries as it veers across the road avoiding potholes. After breaking down twice on the way we finally reach Goma.

To Rawanda

We take the next day off talking to the passengers of the overland trucks which have arrived in the camp. We wander around town and manage to sell one of our old tyres for £20. This buys more cheeses and some bread called “pain special”. Next morning we head out to the north side of Lake Kivu and the Rwanda border. Heaven awaits us if only we can get a transit visa as then it’s asphalt all the way to Tanzania. Our two transit visas end up costing us two old Michelin inner tubes. We head out north-east on a perfect road recently built by the Germans. Rwanda is a small, country where everyone seems busy – even the men are working. It is a cold morning at this higher altitude and we stop to put on jumpers and then to pump up the tyres.

The land is very intensively farmed with coffee the major cash crop.

Every hill we can see is terraced and planted right to the top. Kigali the capital is a sprawling, low and modern city built on a hill and inundated with cars that take no prisoners. We leave heading south-west and by now are enjoying speeds of 50mph which earlier in the day had seemed terrifyingly fast after a thousand miles in Zaire at a maximum of 25mph. The road we are now on was built by the Belgians long ago and is lined with tall regularly spaced trees.

As we reach the border, we meet lots of Tanzanian trucks and pass one that has just overturned after a tyre burst.

We stop to help but the driver says he’s OK. Most of the trucks are out of Dar Es Salaam. By this time of day, the Tanzanian border is closed and we camp there the night. We are both in excellent spirits some five days out of Nairobi. Over a large meal we pore over the Michelin map and Leigh suggests we go to Gaborone in Botswana later returning and flying home by way of Nairobi. We get talking to a lorry driver who is also stopped at the border for the night and he says that the road down the west-side of Lake Tanganyika is good and we decide to head to Gaborone.