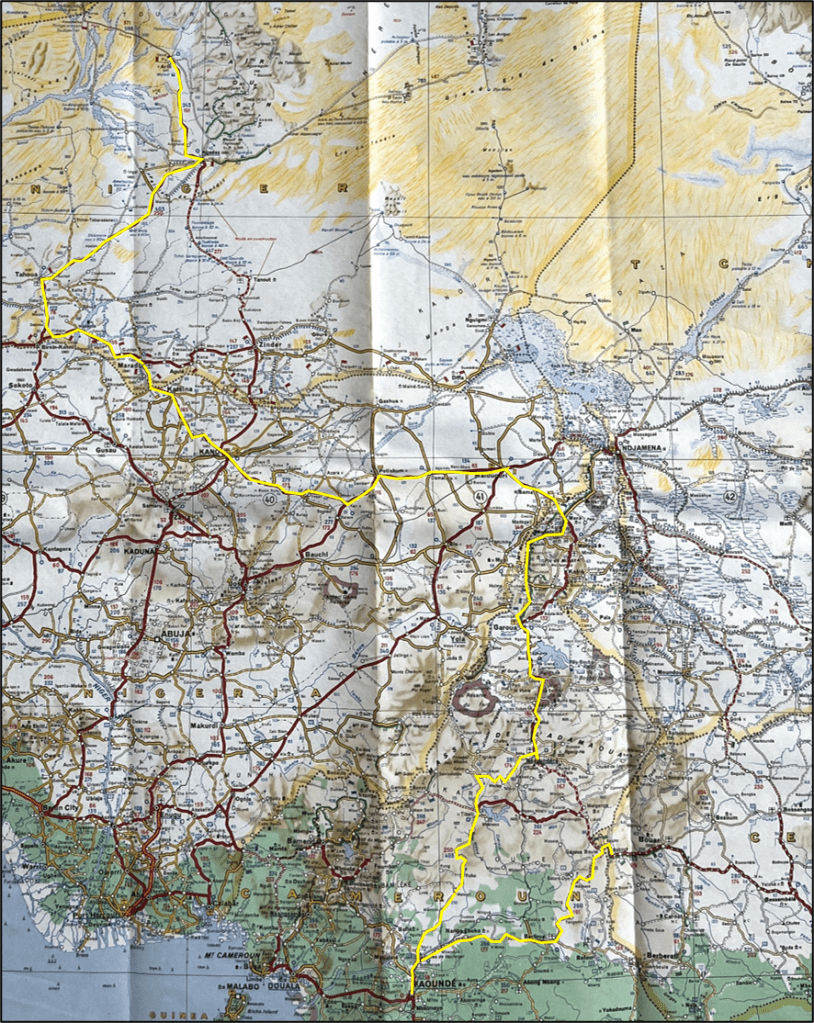

Map of route

Niger

We arrive in Agadez and change money and make the obligatory report to the police. We have our passports stamped just as the inmates of the police cells behind are being fed. Food is being pushed into the hands that have been grabbing at the grille all the time that we have been waiting. We meet the English lads and go to the campsite where we are immediately met by Touareg selling swords, crosses, enamel brooches and carvings. This feels like a real change as no one in Algeria tried to sell us souvenirs. Here it is different and every tourist is a rare source of income.

The next day the lads are headed to Niamey, the capital of Niger, in the west while we plan to go south to Zinder. We start out early, say our goodbyes, we say that we will meet on the beach at Kribi in Cameroun. At the Zinder exit we are told that the piste is easy but it turns out to be very corrugated and we turn back after 10 miles. We then slog it down the asphalt to Tahoua.

About lunchtime we stop for chiy. It is very hot and it has been hard going all day. We already seem to be running to get out of Niger and into the Cameroun. Leigh has reluctantly agreed not to detour up on to Air Plateau and Iferouane. Something is wrong and will remain wrong for a long time. I think that we had too good a time in the desert and before that. We expected it to be hard and so it was but it was also very enjoyable. This is hard too but there appears little to see or do except pass through. Over chiy we talk to a Frenchman accompanied by two soldiers who we later conclude must be a senior manager in the uranium mine. The young man who runs the restaurant asks us where we are headed after Niger. We say Nigeria. He has been to Kano and says that it is a lawless city and dangerous for a white man. Nobody seems to have a good word for Nigeria.

We arrive in Tahoua battered and depressed. We get petrol and buy some fruit and visit the police. We try to find the campsite and are dragged around town by a boy on a bicycle. He takes us first to a couple of places before we are shown the camp itself which is set in an amphitheatre. We give the boy some money and he asks for some pineapple. I churlishly and stupidly refuse even when he asks again. We shower and take the bikes into town for a meal. There we have a disjointed discussion about what is wrong. We return to the camp and sleep under the stars. The next morning, I awake and immediately realise my leather jacket is gone. We both wander around looking for it. Leigh finds it under a tree with only my passport inside. I go off to the police station in Tahoua and report what is missing. The police decide to come to the camp ground as they have had a lot of trouble there recently and escort me back by a different route. On the way we pass a knot of people and stop. Lying on the ground is the rest of my stuff including the cheques but minus the cash. I am amazed to have got this much back and follow them into the camp where they immediately arrest the three guards. Leigh and I agree that we have seen the last of the cash and we just want to leave. The police are taking the campground owner to task for all the thefts that are occurring from tourists and we say that as far as we are concerned the matter is over and we do not think that it was the guards anyway. We are sure that it was the boy on the bike as he had seen me pay for petrol from a thick wad of recently changed cash. He also saw that I kept the wallet in my leather jacket which I had foolishly not put in my sleeping bag. Not a great performance all round. We are pleased to leave and I celebrate by falling off trying to avoid a car that turns right suddenly.

We head south and then east aiming for Maradi near the border with Nigeria. Leigh manages to lose his sleeping bag off the back of his bike. Five minutes later we go back but it has already vanished. We arrive in Maradi, see the police and head down to the camping ground. This turns out to be an expats club with a sign saying “No Camping At All”. This is not quite what our frayed nerves need and we plaintively ask if we can stay in someone’s garden. A French-Canadian guy is the first to break and says that dinner will not be ready until 8pm so we would have to wait. This we do and a Coke and Fanta are brought for us. We are told to go for a shower or would we prefer a swim? Our elation borders on hysteria. When we leave, Jean our saviour travels pillion with Leigh. We are served beef stroganoff and crepes for dessert. Jean is a construction engineer who has worked all over the world although he cannot be much over forty. He is surveying in area for the building of pylons for an electricity supply project which will serve the areas around Zinder and Maradi. Instead of producing their own expensive electricity it will be imported from Nigeria which has plenty of spare capacity from an underutilised hydro-electric plant close to the border. He is a larger-than-life character who is full of statements about the world, life and Niger. Next morning we all get up before dawn. If we thought that yesterday was hard today, we cross into Nigeria and the fears that we have can really start to take hold. Leaving Niger proves far easier than getting in had been.

Northern Nigeria

At the Nigerian border it is as if we have met our long-lost brothers. We are amazed that the border officials are all so friendly. They process the carnet quickly thankfully not checking to see if it is valid in Nigeria. We are briefly interrogated by a member of the police who is wearing shades. I would have hated to have tried to lie to this guy and was pleased to be able to say truthfully that we are not intending to visit South Africa. That’s it; we’re in and we’re off. We head for Kano and we’ve got nearly all day to get there. Immediately something feels different about Nigeria. There are a lot of cars all being driven very fast. There are advertisements, billboards and schools everywhere. There are numerous roadblocks before Katsina but the police are always friendly and allow us to go on after a chat. In Katsina we see a lot of industrial buildings and pass a steel works as we leave. We head into the outskirts of Kano by mid-afternoon.

Kano is the commercial hub of the north of the country. Formerly the centre for all trade heading north through the desert, Kano is a wildly busy industrial city. In my experience, only Cairo can come close to this for its levels of anarchy. We eventually despair of finding the campground and go to the Central Hotel in Kano for a brief spell of luxury.

As we are unloading the bikes we talk to a French guy who invites us for a drink that evening. We go to a bar nearby. The Frenchman has lived here all his life and appears to have a finger in every pie around town. Over dinner of gusii and n’shima in a local restaurant he tells us a bizarre story of his aunt and uncle and ten of their family who died crossing the Sahara five years before. We’re not sure if we believe the story but his girlfriend who seems sane enough doesn’t give anything away so maybe it’s true. The next day we have a good look around Kano. The city is a melting pot for the continent. It is a mixture of the old with its vast bustling open-air markets and the new with modern banks and a full range of goods in the stores. We buy books, food, bags and generally sort out things that are only possible in a large town such as this. That evening we dine in the hotel on a not very adventurous Chinese meal. Our plan is to drive to Maiduguri some 400 miles due east the next day. I manage to delay us by over an hour by losing the bike keys. We make good time all day travelling through Northern Nigeria and even have time to stop for lunch in Potiskum. We are still in very flat country, the huts made of mud and the villages looking very much like those in Niger.

Each village has groups of men sitting around and invariably they wave to us as we pass. The fields, instead of being barren as they were farther north, are intensively cultivated. As well as the low scrub there are taller trees including knarled baobab and there are many termite hills. When we stop, we are always asked where we are from with an interest and warmth that we only meet again much later in Tanzania and Zimbabwe. Nigeria does not rely on tourism and consequently we are treated as travellers and shown much consideration. Although we never ventured into the south, people we meet said that the stability of the Hausa and Fulani tribes now made the north quite safe and relatively prosperous. We reach Maiduguri by early evening and find a good hotel there. The following morning, we have the best breakfast for a long time and set off south to the Cameroun border. At Pulka the asphalt ends and we wind high into the mountains to the border post itself. Leaving Nigeria proves to be a problem as Leigh is described on his passport as a student but has no Student I.D. card.

Northern Cameroun

Eventually we convince the official we are not spies and cross the dry river bed into Cameroun only to find the border post shut for the day. The afternoon is spent making tea and reading, the evening making food and reading. There are numerous comings and goings by various officials but nobody wants to sort us out on a Sunday. At first light the next day we are given our passports duly stamped and are sent on our way. At the first customs post the official is having a shower so sends us on to the nearby town of Mora where our carnets are processed under the bored gaze of a group of soldiers. We head off to Maroua, one of the principal towns in Northern Cameroun, to change money and stock up with food. The French have left their mark in many ways in Cameroun and one of the few positive ones is the proliferation of good bakeries where you can buy croissant and pain au chocolat. After ransacking a bakery, we head back up north to get to the famous game park of Waza. By now we are encountering road blocks frequently and at the entrance to village of Waza we are compelled to surrender our passports to deter us from making the 40-mile dash to the border with Chad. While we drink a Coke in a bar and chat to a local soldier there is a brief storm which turns the road in to a mudbath. We then try to sort out an entrance to the park but are told that it will cost us $120 to hire a Land Rover and that bikes are not allowed in. We head off into the bush nearby and camp after doing a long overdue oil change.

Up and off early the next morning we pass back through Mora and south west into the mountains. The gravel road becomes narrower as we head into the hills and by the time we reach the volcanic region around Roumsiki it was quite slow going. The vegetation becomes lusher the higher up we go and the round mud huts of the many villages that we pass are well constructed and carefully decorated.

All day we head south on mountain tracks before stopping 30 miles north of Garoua. That night as every night in Cameroun there are tremendous displays of lightning with discharges continuing for hours all around. We pass through Garoua the next day and take the asphalted road south. On our map is a sign that elephant can be seen 10 miles east of this road by a large lake. We head down the track that leads to the lake but we arrive at the village nearby we are told that is a centre for hunting elephant not seeing them; not at all what we want! An uneventful day’s ride takes us to N’gaoundere and the Railway Hotel.

Leigh has a cold which by the middle of the night has turned into a major bout of shivering and by the next morning he is wearing two jumpers and sweating profusely. We work out from one of our disease survival books that he probably has got some form of malaria. While he rests the next day I go round the town in search of a boot repairer. Later on that day we meet two Peace Corps workers whose parents are staying and we voraciously consume the relatively recent copies of Time and Newsweek that they have with them. We head off south on dirt roads next day passing two road blocks before we even manage to leave the town. At our first stop three hunters have just shot a monkey and carry it slung over their shoulder. They laugh at us when we say that we have no way of carrying it or cooking it and continue down the road to their village. We potter on slowly and reach Tibati by mid-afternoon.

South to Yaounde

There is nowhere to stay there so we continue down the track towards Yaounde, the capital of Cameroon. The transformation in the vegetation is now complete and we are on the edges of the rain forest. Gone are the tall thin grasses and the foliage along the road side is dense, lush and a very dominant green.

The bush is thick with many trees. We come across few villages on this stretch and everyone we see waves as we pass. The women wear long bright dresses made from a single piece of cloth. The men wear T-shirts and long cotton trousers or occasionally shorts. Nearly all of the men carry a type of machete called a panga. We stop before dark and set up our inner tents in the woods to keep off mosquitos. We cook our usual combination of vegetable stew adding a soup for flavour along with pasta. Although there has been much lightning early on it stops by mid-evening and we go to bed. About midnight, the downpour begins and 30 seconds later I am lying in a pool of water 2 inches deep. Even Leigh has woken up by this time but is less wet. I get up, put on dry clothes, all my waterproof riding gear and lie down by the tent until dawn arrives seemingly about 10 years later. That morning’s ride is very hard. It is still misty from the previous night’s rain and the woods are steaming as the sun heats up the sodden vegetation. The red mud from the track clings to our tyres, blocks our treads and fills the gap between the front tyre and the mudguard. We have to stop and clear it. It is only later that that we can go quickly enough for the tyres to stay clear. The surface of the track is so slippery that when we get to uphill sections we have to push each other’s bikes and it is impossible to make them travel in a straight line. Two hours before dark we are only 30 miles from Yaounde but discover that the ferry marked on the map is no longer working so we must make an additional detour of 30 miles to get to the main road to the capital. This stretch on the gravel road in the dark proves to be one of the most frightening of the whole trip. There are cars passing on either side of the road mostly without any lights at all and our vision is further obscured by the clouds of dust that they throw up. We finally manage to get to Yaounde in one piece and find a hotel, grab some food and collapse into our beds.

Each day that we stay in Yaounde there are spectacular storms which obliterate the sky and leave behind beautiful cloud effects and sunsets of the deepest crimson. Yaounde is a city surrounded by hills whose sides are packed with dense vegetation. We plot out route through West Africa and the relatively low price of a Central African Republic visa finally ensures that we will head east as we originally planned rather than go south through Congo. We fit our new rear tyres, eat our last croissants and direct our by now collapsing bodies but still perfect bikes east for the long trek through the rain forests of Central Africa to East Africa.