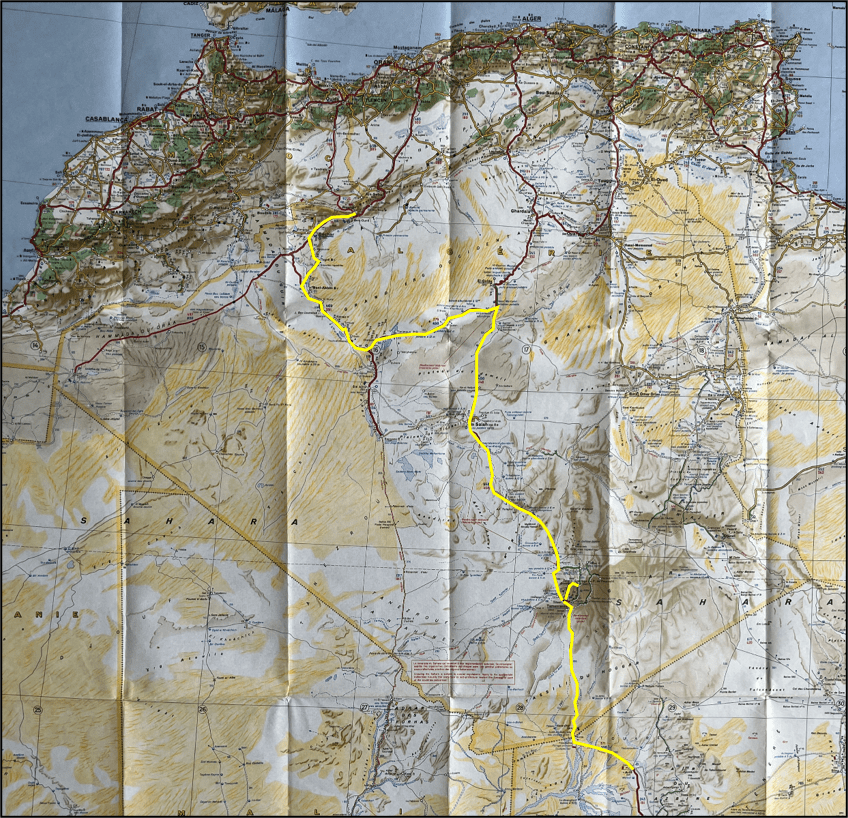

Route through Algeria

North-West Algeria

We head south along the line of fortifications that the French had built all along the Algerian-Moroccan border in the late 1950s to prevent arms and support reaching the Algerian Independence Movements.

We pass through Bechar (formerly Colomb-Bechar) and leave the main road to visit the oasis town of Taghit.

The town is situated right at the edge of the Grand-Erg Occidental, the great sea of sand dunes that extends for many hundreds of square miles to the west of the Route du Hoggar. It is a wonderful moment and a scene that can have changed little in hundreds of years as you reach the brow of a hill and see the enormous bright sand dunes acting as a backdrop to the pale, squat buildings of Taghit. In total contrast to the dunes is the green of the palmeraie and the oasis which gives life to the desert. We drive up to the hotel and offload the bikes and hand over considerable amounts of our ridiculously overvalued dinar. The hotel is much recommended and has many visitors. It is run by the Taghit town council rather than by the Algerian State Tourist Company. After a pleasant meal of chicken, rice and salad I wander round the town in the moonlight with the dunes silhouetted against the night sky. It is quiet except for the hum of the generators that power the town. The next morning, we head for the dunes and spend half an hour climbing the 300ft of the closest dune. It is hard walking as your feet sink into the sand and we are unable to master the Touareg technique of gliding over the sand and applying very little pressure through our feet. We reach the crest and gaze upon the sea of dunes stretching for miles to the horizon. We sit and stare for a long time before plunging down through the soft sand and back to the town. We pack up the bikes and are about to leave when we start chatting to an English woman who lives and works in Algiers. She is here on vacation with her family and says how much she enjoys the chance to get out into the desert. We are desperate for any information and ask about the towns and campsites en-route. She is amazed that we want to know about campsites as you can just stop whenever you wish and bed down there for the night. We say that we are concerned about scorpions and other desert animals at night. She replies that she has been camping out with her children in the desert for the last six years and has never had any problems. She advises us to look under the nearby stones and rocks to make sure there is nothing around, unroll our sleeping bags and to stop worrying and enjoy ourselves. This we do that night and so begins three great weeks of camping out in the desert.

We head as far south as Beni Abbes which is one of the few major towns on the northern asphalted part of the Tanezrouft, the route leading eventually to Mali. It is a Saturday afternoon and the town is disappointing and depressing in a way that Algerian towns seem to specialise. We have not yet learned to steel ourselves to the emptiness of people and life out-and-about in Algerian towns. We are used to Moroccan towns and expected more of the same. With the exception of Tamanrasset, the Algerian towns which we visit feel less enticing and enjoyable than the desert itself. In Beni Abbes we spend a couple of hours at the museum which has excellent displays on the climate and geography of the Sahara and its flora and fauna. Included is a spectacular array of every type of insect and scorpion which you never wanted to see and some very large stuffed vultures. In addition, there was a zoo containing a fennec, a bat-eared desert fox as well as a botanical garden with very little living matter but lots of sand. The wind has got up by now and the sun is obscured for the first time on the trip. It has become very lonely with a palpable sensation of total emptiness.

We ride up to the hermitage of the French monk Charles de Foucauld where he lived prior to walking hundreds of miles to the south-east and founding a hermitage at Assekrem in the Hoggar Mountains. We then go to have a coffee in the hotel which overlooks the town. The hotel is drab and empty and fits the mood of the rest of the town, and is made worse by a football match commentary going on in the background. Mentally this is rock bottom for the first time. We drink up quickly, pay, fill up with petrol and some water and leave the town. Back on the main road things seem more manageable. We drive on for another hour or so and as it gets dark pull off the road behind some piles of gravel being used for roadworks. We are meticulous about not being seen as we leave the road and duck out of sight on the few occasions that cars or lorries pass. Although we will camp in the bush many times afterwards this is the first we have done so and we are paranoid about camp safety.

Only later after it is completely dark do we begin to relax. As the full moon rises, we do as instructed and unroll our bags and lay down to sleep. Firsts are always memorable and we both find out that night that silence really does exist and there are places on earth where from horizon to horizon there is no light at all. To sleep outside in the desert is very special.

Nights spent in the bush in Africa appear long and the arrival of dawn goads you into immediate action and early starts.

By now we are packing up quite quickly and after a cup of coffee we set off even though it is still not seven o’clock. We drive the bikes back on to the asphalt and stop to check the oil. From the north a loud thump-thump-thump can be heard and eventually a Yamaha Tenere comes into view. A large man wearing a boiler suit gets off and greets us in German. Carl is on a two-week vacation from Stuttgart via the desert. We chat together for an hour or so in very broken German and then drive off together. We stop at the next town and we share his wurst and he, our oranges. He says that if we are sensible and stick to the asphalt as much as possible, we should get the bikes through but that we are carrying too much stuff. The secret of driving in the sand is “gas geben” (give it gas) and not to worry about the front wheel and to drive at over 100kph through the sandfields. He says that we have to take a stick with us for use at the Niger border against the children who pelt you with stones as you struggle up the sandfield hill there and above all “Immer gas geben!”. Carl is intending to get to El Golea in the Hoggar that night so will go on a little quicker on his own. We say our goodbyes and he blasts off south. We follow him a little later after taking a wrong turn out of town. How we manage this we are not quite sure as there was there is only one route! We plod on at our customary 50m.p.h. checking oil and tyres occasionally in the high 30-degree temperatures. Since mid-morning it has been windy but now the horizons become obscured as sand begins to fill the air. Our worst fears of a sandstorm seem about to be realised. We try to remember the sections on Sandstorms in Melville’s Stay Alive in the Desert but can only recall How to build a latrine. It remains windy all day and sand is constantly whipped across the road but rarely settles. On one of the few occasions that it does I try to gas geben through the sand and promptly fall off. Relatively undeterred we turn east off the Tanezrouft and headed for Timimoun and the Route du Hoggar, the great road south.

We arrive in Timimoun and our spirits plummet. It is a dull, sandy and very morose Sunday afternoon. We find the campsite and set up our tents. We decide to begin to reduce our luggage and give some maps away to our fellow campers and leave some clothes at the entrance to the campsite. We take an hour or so over an oil change and cook our tea. That evening we chat to a French couple who are hitching around Algeria.

Morning brings a clear windless day and we are ready for day’s first attraction, the fabled Circuit of the Sebka villages, the old settlements in the palmeries which are dotted around Timimoun.

We load up and set off down into the main palmeraie. We drive around and end up lost in a tiny village whose inhabitants give us a “You’re not from around these parts look”. We return to Timimoun and set out again. We turn off the road as instructed and soon are ensnared in our first sandfield. We push each other through but are both already in bad moods. We gun the bikes and in half an hour do three kilometres. As yet we have seen nothing but sand and the vast valley floor promises little else. A Lada Niva putters easily past us and on up the valley. We now know we’ve got no chance and head back to Timimoun. I try and go a little faster through the sand and succeed only in ending the short and inglorious life of the cat carrier. This is now a mass of severed plastic-coated wire. A brief ceremony marks its demise and bungies once again do the job. Back in town we drink chiy and walk around the ruins of the ancient hotel which is constructed entirely of red mud brick. It is being renovated after collapsing five years earlier. We head west stopping to try to sell some clothes at a petrol station. We chat for a while to the owner and buy some beans for the night’s meal. Later we come across some untethered camels grazing along the side of the road.

The Route du Hoggar to Tamanrasset

We reach the Route du Hoggar in early evening and head south pulling off to camp just before the road starts its rise to the Tademait Plateau which is a vast waterless plain.

We are more relaxed this evening and chat long after going to bed. Yet again we go over the exact range of items which we must discard to reduce our loads. The desert is vast, quiet and dark made an eerie yellow by an enormous full moon. Occasionally I am awoken by the roar of the trucks climbing up on to the plateau, their drivers preferring the cooler air of the night. We are once again up and off early after camping out. This the best time of the day, riding in the cool of the morning. After an hour or so the road disintegrates and we ride on the piste parallel to the broken tarmac. It is quite hard hammada, stony desert, and we make slow but reasonable progress. Other cars and trucks are strung out all over the plateau seeking the least sandy or corrugated areas. The road returns as a narrow strip of tar and holds up until we fall off the southern end of the plateau and see stark wind-eroded mountains to the west. We ride on to In Salah where we stay in the expensive government hotel unable to face a night in the sand sodden campsite. I phone home that evening as it is my birthday next day. We eat the hotel set meal in and I open my cards. We are full of trepidation for the 450 miles to Tamanrasset most of which we know will be non-asphalt track. We are off by 7am and make good progress in the morning. Apart from one long section of sand which bars the way, the road is tarmac. Later this becomes broken and potholed but it stays easier for us than for the cars which we meet as we weave a way through the tarmac remaining. At about 100 miles out of In Salah we are amazed to find a restaurant in a tin shack along the route. We stop and are welcomed by a Frenchman, M. Jean and his Touareg companion. We have a meal of omelette and salad. M. Jean tells us that he has been here for seven years serving the lorry drivers and tourists making the run to Tamanrasset. As we leave, he asks us to take a letter to the service station Arak further down the road.

Later we are amazed to see some flowers and plants alongside the road. The scenery changes constantly with dark black stone hills jutting out of the sand. In some areas the dunes of small ergs are stretching almost to the road. We enter the Arak Gorge with sheer cliffs all around us and stop to deliver the letter we had been given. There is brand new asphalt as we leave the gorge but eventually this ends and we follow the old tracks as they weave in and out of the hills in a vaguely southerly direction. We pull off the road around dark and prepare to camp. We are joined almost immediately by M. Rafou a Touareg who is working on the new asphalt road being built to Tamanrasset. He returns later in the evening after we have eaten and brings the cups, leaves and pot needed for tea making. He has been working on this stretch for two years and will be here for two more. He lives in In Salah although his family is originally from El Golea. He has travelled throughout the Sahara and Sahel and has been as far south as Kano in northern Nigeria. We drink numerous cups of sugared tea and he tells us stories which are hard for our French to understand. He camps with us that night and goes back to the construction camp at first light.

That next morning proves to be hard as we drive over long corrugated stretches which every so often give way to sand. We are by now drinking lots of water. We stop frequently to make up more water using our Katadyn ceramic water filter and add sugar and salt to replace what is lost by our constant sweating. I again try to go quicker in the sandy sections and reach the giddy speeds of 35mph before the front wheel disappears in and the bike and I go our separate ways. I am OK but the bike now has a twisted chain and adjuster. Leigh says that it was a great crash and well worth staying behind for. I spit out sand for the next half an hour and go along at a maximum of 20mph. Later we reach the square white-walled tomb of the Marabout Moulay Hassan, a holy man who died here on a pilgrimage to Mecca.

All vehicles that pass this way must circle the tomb three times or are doomed to fall foul of the desert. It is a strange sight to see buses and lorries racing round the tomb before everyone gets out to have a Coke or a chiy. A short distance on is the wreck of a burned-out VW Combi which paid the price for not obeying the custom when all its metal jerry-cans mysteriously caught fire! By mid-afternoon we reach Ain Ecker an old fort where the tar road starts again and lasts through the Tropic of Cancer and until 20kms before Tamanrasset.

Tamanrasset and the Hoggar Mountains

By the time we reach Tamanrasset it is dark but we are euphoric. However much further we manage to get at least we made it to the heart of the Sahara. We find the municipal campsite and go for a single celebratory beer which costs $3.

The next day we straighten the bikes out, change the oil and fit a new set of sprockets and chain. It becomes clear that a second cat carrier funeral is approaching. We spend a long time chatting to three young English guys who are travelling through North Africa in a Land Rover prior to going to college back in England. Their desert regime is unusual as they never go to bed before midnight and never get up much before midday. They tell us that they had abandoned their attempt on the Circuit of the Sebka villages after nearly rolling their Land Rover three times.

We had heard a lot about the hermitage at Assekrem which Charles de Foucauld had built high in the Hoggar Mountains after his 600-mile-long trek from Beni Abbes. He continued to live there amongst the Touareg until his murder by renegade tribesmen in 1916. The hermitage is perched at the highest point in the mountains. Most of its visitors come to witness the beauty and tranquillity of the desert dawn and dusk for which it is renowned.

Our drive up to Assekrem is accompanied part of the way by an Englishman riding a powerful Paris-Dakar BMW replica. We have a hard time at first on the corrugations but later the lightness of the 250s makes the rocky tracks further up into the hills enjoyable. The worse the piste becomes the more fun we have and by the end we are out and out racing to reach the hotel below the hermitage first. Some German bikers stand agog as we jabber on about the ride up that we have just had. The Englishman shakes our hands and says that he is amazed that we have managed to get up on these bikes. The evening spent there is wonderful as we all share couscous and tagine and all our far-fetched stories of how we have got here. That night we sleep out and get up early to witness the dawn and sunrise over the Hoggar.

Leigh has not managed to survive the previous evening’s meal and is suffering from diarrhoea and vomiting. We decide that it is best if we head back to Tamanrasset as quickly as possible as there is nothing in the way of help at Assekrem. Leigh is so ill that the first 10 miles take a couple of hours. It is clear that he can go no further and we hijack a lift for him with a party of French travellers in a Nissan Patrol. One of this group offers to ride Leigh’s bike as far as possible and manages 20 miles before he and the rest of his group take a different route off into the mountains. In Tamanrasset Leigh is examined in the hospital and is eventually put on to a drip to put back some of the fluids that he has lost. I dump my bike and get a lift back up the track with some Touareg guides to rescue the other bike. The Touareg act as though it is a matter of course to take me back and will accept nothing for all the help they have given. Eventually I get the second bike back and the doctor sends me to get some medicines from a pharmacy.

Tamanrasset has easily been the busiest town so far in Algeria but I have seen nothing until I enter the pharmacy which is crowded with almost 50 people waiting to be seen. Of the medicines that I have been told to get they have only got Flagyl but this is acclaimed as a panacea for all stomach disorders and getting hold of it is well worth the wait.

Crossing the desert proper

Also staying in the campsite is a herd of assorted Mercedes, Peugeots and an old MAN truck all being driven down to West Africa by a group of Germans. We are not convinced that our bikes will make it through the 450 miles of sand and corrugations to the start of the asphalt in Northern Niger and ask if we can put the bikes in the back of the truck for that part of the journey. Bobby says that it is his truck and if we want to give him some hard currency then it is OK with him to bring the bikes. His decision is helped by the fact that he has already agreed to give a lift to one Emilio Scotto, a round-the-world Argentinian motorcyclist along with his Honda Gold Wing so another couple of bikes will make little difference. Bobby says that they are leaving the next day.

In the morning, Leigh seems well enough to travel and we load the bikes on to the lorry at a municipal rubbish dump. By 4pm the whole convoy is just about ready to roll and we head into the town to buy some more provisions and to check out of town with the Tamanrasset police.

Our caravan leaves town consisting of one MAN truck, two Mercedes cars, one green and one blue, three Peugeot 504s, one green, one blue and one maroon (an automatic fuel injected car is not a first choice for the desert). By nightfall we have reached the end of the asphalt 20 miles to the south where we sell gear oil to some Algerian truck drivers. As they have not asked us to camp with them, we move a little farther on. We can quite understand their reluctance. The following day we are off by 9.30am, the best part of the day long gone. I am with Tomas in the maroon Peugeot hammering along at 50mph over the hard sand surface. At some point in the morning someone realises that the green and blue Peugeots are no longer with us. An hour’s furious argument in German follows and we then we continue on until 2.30pm when a two-hour lunch break is taken. After another half hour driving the maroon Peugeot stops never to go again.

Tomas is accused of driving too fast in the heat and cracking the cylinder block. There may have been a little truth in this. When asked if the cylinder block from another engine which is festering in the back of the Peugeot could be used, I am told that this was the original engine that Tomas had blown up a week previously. Oh.

We camp there that night still minus two cars. We make an early start the next day and are off by 10am with the truck towing the Peugeot. Progress is quite good until we come to a car graveyard, a stretch of deep sand through which everyone must funnel. There are carcasses of Peugeot, Mercedes and Citroen littering the piste for over a kilometre. We meet two French guys whose Peugeot has just expired and who will need a lift south from here. Two hours after being abandoned their car is well on the way to being a carcass too. Any lorry driver will strip a wreck and sell the parts on. The maroon Peugeot becomes detached from the truck and half an hour later Bobby comes back having noticed that it is missing. Later we make a brief stop at a Peugeot carcass to take a fender off it to replace a dented one on the green Peugeot (where-ever that may be). We reach In Guezzam, the border town between Algeri and Niger, by mid-afternoon amid shrieks of delight as we find that the others are already there. Some welding repairs are carried out and the car‘s battery explodes. We walk round In Guezzam. There is a massive tented town to the west. As with every town in Algeria there may be little to buy but all the necessary services are there with a hospital, a pharmacy and water and electricity. The country may be poor but the government appears to be trying to maintain a basic level of care for the whole population. We decide to camp outside the town but as we leave in the dark some of the vehicles get stuck. The truck blunders on taking a wrong turn before becoming stuck and promptly being arrested for being in a military zone. The soldiers then come to find out what all the rest of us are doing in the dark. As I speak some French, I am taken to see the chief and explain about the truck. We are all told to go away. This we do and camp further on up the road. After we have all bedded down for the night a truck full of soldiers arrives and we are told that we are still in a military zone. We all go back into town and sleep in a car park. The next day should be simple as all we have to do is to get in the vehicles and go on up to the border post. We set off at 10am and immediately the vehicles become stuck in the deep uphill sandfields. Then the truck gets stuck as well. Big problem. The consensus is to rest until the sand goes away (unlikely) or until something else happens. We are not convinced that will happen and set about digging the truck out using the sand ladders – perforated steel planking (PSP) – and eventually we free the truck and head up the border post. There is yet more confusion when we try to explain to the border officials about the bikes that are in the truck; they seem to suspect that a mercenary army is headed south. There are by now 12 people in the group. Once cleared, we speed over the 10 miles to the infamous border post at Assamaka that has been the source of numerous stories about people being kept there for a week with no water.

We arrive and begin the complexity of entry. First comes the customs search. Later the immigration chief decides that he wants Tomas’ spare engine. We are told that we will have to wait until the next morning before we are free to leave. This comes as no big surprise. The next morning the immigration official becomes the owner of one hardly used Peugeot engine and we all hope that we’re not around when he actually finds out just what he has paid for. The last part of the entry is proof of funds which the Germans bluff their way through with their usual flair by passing the same wad of money to the next person as they go see the official in charge.

We are ready to leave and we take the vehicles down to the border and wait. Emilio gets bogged down in his latest choice of car. Finally, we leave six abreast racing across the flat plain following the line of balises which mark off each kilometre. Somehow Bernt and I get left behind in the green Mercedes and see no one for about an hour. Later we come across Emilio and the blue Peugeot which has broken down in a sandfield. The fuel pump is broken and Emilio is terminally beached in the front seat. Johann and Jurg return in the blue Mercedes. By now we are all experts in Peugeot fuel pumps and we soon repair it. The car starts but goes nowhere because at this point the clutch burns out. Bernt and I remain with the car settling down with cassettes, food and ample water while the others go on to Arlit to fetch the truck. Just before nightfall two Lada Nivas arrive and we camp and eat together that evening. It is amazing how everyone makes time to help you out in the desert and the evening passes by as if is being spent with old friends.

Around 9am the next day the truck arrives. Istvan says that it is his car and that he’s going to leave it there if he wants. His mood is made even worse when the truck becomes stuck trying to pull the car out. We stop for water. More people arrive. These most recent arrivals include two white Peugeots, an English Combi and the piece de resistance, a Jules Verne type contraption with trailer piloted by three Frenchmen who are attempting world canoeing records on the Zaire and Zambesi rivers. This vehicle has a 250-metre steel winch which when coupled to its 5-litre Chevrolet engine pulls out both truck and car. The Brits in the Combi come into their own and serve tea to the assembled group now reclining under a Bedouin canopy strung between the cars.

Progress is then good until Istvan drives the truck through instead of round a sandfield and the steel planks get a workout for next three hours. After we have raided the truck’s foodbin we settle down to dinner and another night under the stars. We arrive in Arlit the next day around 4pm amid much rejoicing. It has taken 7 days to do 700kms. Once I had learned that it did not matter how long it took to get there and that just being in the desert was wonderful, I had a great time. It is very windy in Arlit and the sand is getting everywhere. After showering it is like being in a giant hairdryer. The temperature is 47 Celsius. We all meet up in Arlit for a meal and find the three English guys in the Land Rover and have a hilarious time recounting our tales since the last time we were been together in Tamanrasset. The Germans bring some local girls back to the camp and they all argue half the night who will pay for what.

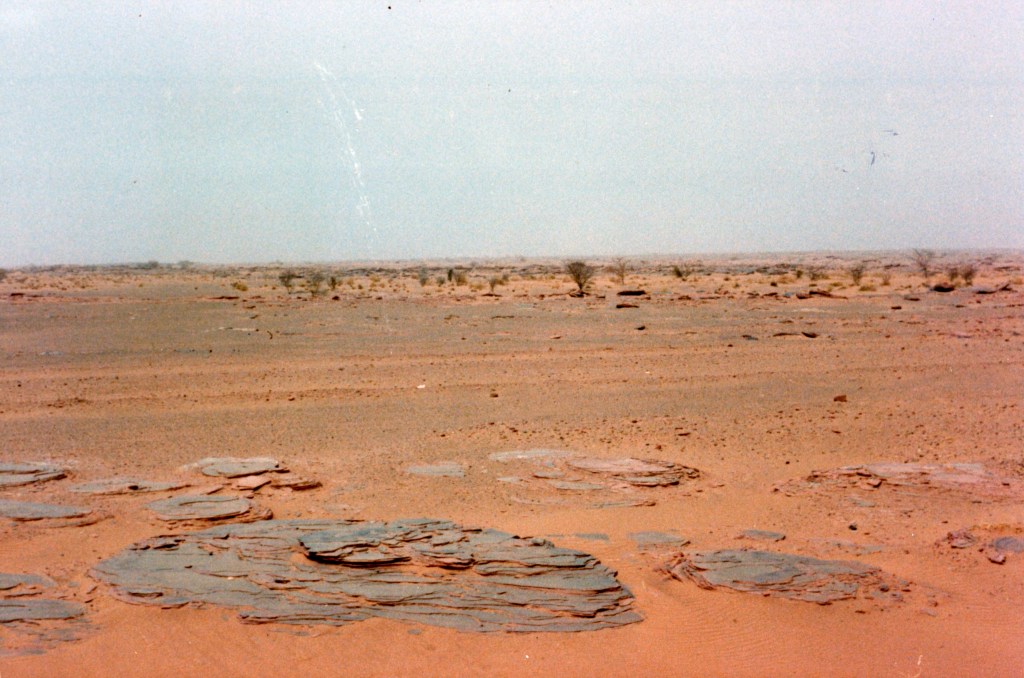

The previous afternoon we removed the bikes from the back of the truck and inspected them for damage from the tremendous buffeting they had had across the desert. The next morning, we change a little money and buy some insurance which is compulsory. In Niger the road to Agadez although dull has perfect tarmac. There is a uranium mine in Arlit and this “yellow cake” road is crucial to Niger’s exports. In fact, some 90% of the country’s foreign exchange earnings come from this one mine. We are now at the end of the Sahara and at the start of the scrub of the Sahel which stretches to the rain forest hundreds of miles further south. Some acacia bushes begin to appear along the road.