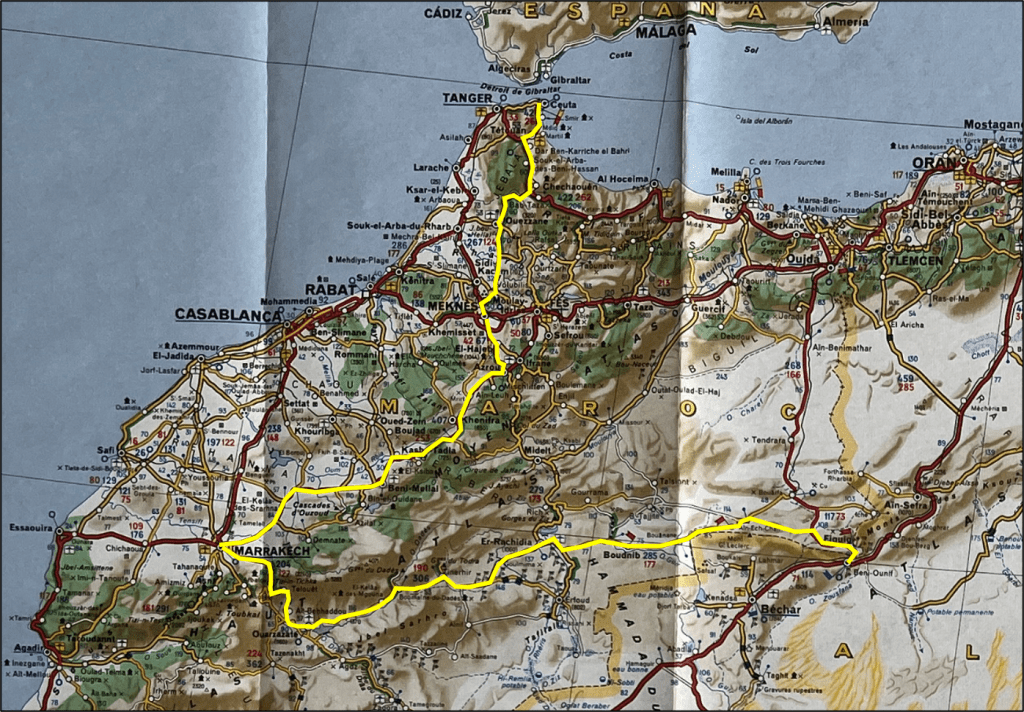

Route through Morocco

The mountains of Africa are visible even before the ferry has passed Gibraltar and its enormous slab of rock.

Northern Morocco

The sea is a deep blue and the mountains are stark points of sandstone jutting out of the heat haze. These are wonderful moments as the Maghreb introduces Africa as clean, bright and excitingly Arab. Before you plunge headlong into Africa you have still to survive the duty-free port of Ceuta brimming with people buying and selling every conceivable sort of electrical goods, clothes and bottles of drink. You cross the chaotic border into Morocco and suddenly you really are in a new world. The Mediterranean coast is left behind along with its new tourist village developments we begin to climb into the Rif Mountains.

I had last seen Morocco five years previously in the autumn when everything was dried out. In spring, the Rif Mountains are green from recent rain; red and yellow flowers form a carpet that stretches across the hills. The whole of the Maghreb and even the desert itself has had a lot more rain than usual so far this year. We stop for lunch in a cafe along the road overlooking a large reservoir and have a meal of chicken and rice.

As always, we study the map. After our chat with the desert rover in Plascencia we have decided to travel around Morocco and to into Algeria at Figuig in south-east Morocco rather than drive along the coast road. People who have only travelled through this northern region to the east rarely enjoy Morocco. The hashish sellers are aggressive and are rumoured to slash tyres to make travellers stop and buy. Riding due south from Tetouan to Meknes we encountered few people selling hashish. Towards the end of the day we pass Volubilis the old Roman capital of the Maghreb and Moulay Idriss the earliest Arab capital – a stone-built town perched on the sides of the hills.

Meknes contains a real delight – the best campsite north of Zimbabwe. It has deep grass, hot showers and the friendliest of owners. Even though we arrive late we are able to have a tagine – chicken or meat stew with rice – in a building resembling a Bedouin tent. The next day we tour Meknes. Itself a former capital, it contains the palace and prison of Moulay Idriss a ruler of the region 600 years earlier. We are shown further round the city by three Moroccan students with whom we speak a random mixture of English and French and shared a number of Fanta and Coke.

To Marrakech

It is over four hundred kilometres from Meknes to Marrakech through the heart of Morocco. Initially you climb gently out of Meknes into the hills of the Middle Atlas. Later you travel south-west along the vast Tadla Plateau. At this time of year the mountains to the south are still capped with snow while to the north-west the plains roll away to Atlantic Ocean. The fields are already full of crops. As the day wears on the temperature rises sharply.

For the first time we are drinking water during our stops and wearing just T-shirts and Jackets. By the time we reached El Kelaa des Srarna it is in the high 30s. Only in Marrakech later in the evening does it cool down. All we have to get used to is another 10 degrees C!

Marrakech in the late 1960s was a hippie centre to rival Kathmandu and Lamu in Kenya. Nowadays it has geared its appeal to much wealthier tourists. Building around the municipal campsite stops only between 2 and 5 a.m. Hotels and apartments are the prime developments but there are also tennis plazas and conference centres. In the middle of the city, however, little seems to have changed in the past thousand years.

At night when the tourist stalls are put away the Djema el-Fna, lit by candlelight, becomes a vast open-air restaurant filled with scores of food stores. These sell soups, chicken, meat, kebabs, rice and any number of fruit to be taken with soft drinks or chiy- a sweet tea. It appears to have been this way since the start of the camel trains brought the goods of equatorial Africa across the desert. Marrakech was then the focal point in the Maghreb for this trade. Thousands of people still throng round the Djema and the surrounding souks until late into the night.

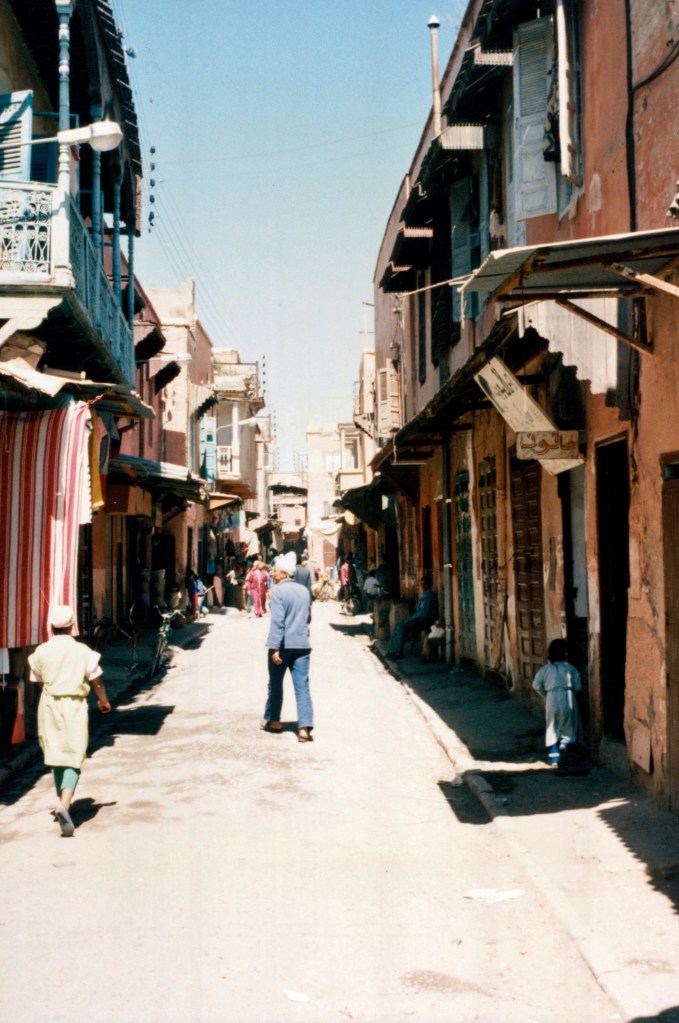

By day the atmosphere is once again that of a large Arab souk. It is the Djema at night that makes Marrakech unique. The souk itself is arranged into areas according to their trade. There are goldsmiths, leather workers, jewellery makers, dyers and weavers crammed together down a mass of narrow alleyways with mosques scattered throughout. Tomorrow we will cross over the High Atlas Mountains into a totally new region and the beginnings of the desert.

Crossing the Atlas Mountains

We agree that we would have a nice easy day and stop in the early afternoon in Ouarzazate. A short hop over the mountains but this is not how it turns out. From Marrakech we can see across the last of the plain until it comes up sharply against the High Atlas Mountain range.

Three high peaks are visible including Toubkal the highest mountain in North Africa which remains covered with snow all year round.

We ride up into the foothills and away from the villages until we reach the highest pass. There are spectacular views mountains all around and Marrakech remains visible away to the north.

Our Michelin map gives us an alternative. We can go either by the main road or by a less well-known road which passes through a town marked with a Kasbah. It is only lunchtime and we decide to go and see the Kasbah town of Telouet. We drive east through a high river valley as far as Telouet and stop for coffee in a tiny restaurant where we chat to the owner and his friends. The Kasbah itself is built out of sandstone mud bricks with small windows set high in the walls and numerous square turrets all set at different heights. It is perched low on a stone outcrop and would have commanded the river that ran through the valley.

Women are washing clothes in the ice-cold water of the river. The river is quite high and bars the way of a track which leads off from the far bank. No matter we agree as there is another track that continues on this side which we can take. Two kilometres later the track gets even narrower and is strewn with rocks. As usual the trip’s major errors occur when I am in front. The track is now only wide enough for a donkey (or a motorcycle) to pass and in addition there is a 100ft drop to our left. This cannot have been what the map had meant. We continue mainly because there is nowhere wide enough to turn round. We round a bend and meet a group of villagers who seem more than a little surprised to see us.

After a good deal of laughter, a couple of the younger men explain that the “main” road does not pass through here and that we will have to cross the river to continue south. They help us turn the bikes around avoiding the long drop and follow us back to the river. We are now compelled to cross the stream. We have already learned the need to reconnoitre in such situations so we plunge into the water to find the shallowest crossing point. We take Leigh’s bike across first.

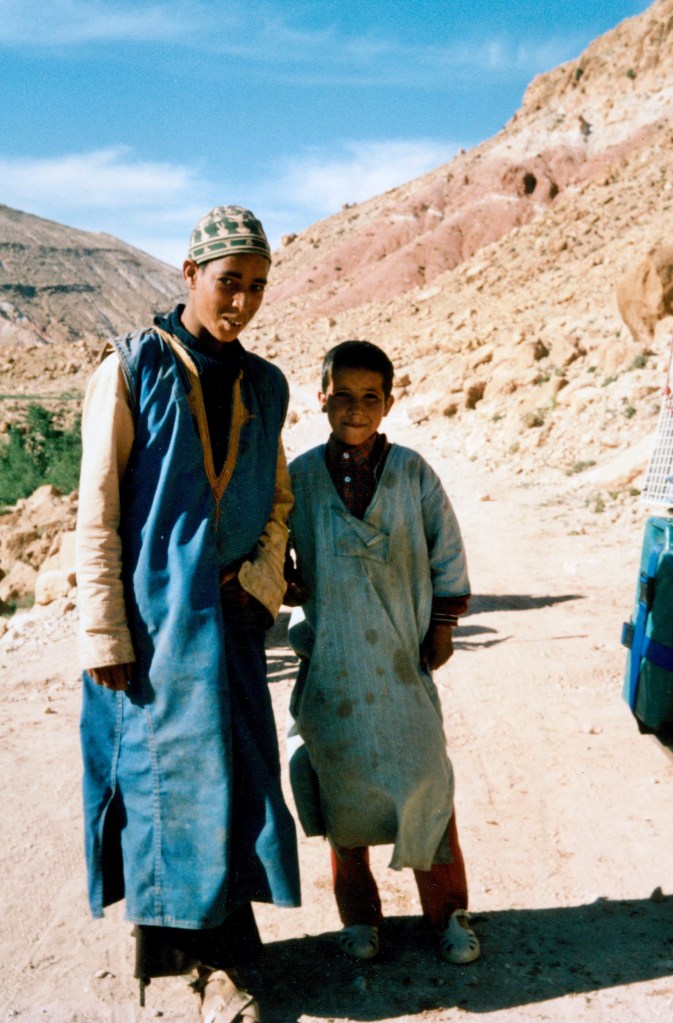

On the far bank two boys are watching and point the best way to go. Leigh gets on and keeps the bike revving while I push. The current is strong and the water comes up as high as the cylinder block. The rear wheel spins over the smooth rocks in the river beneath. Leigh reaches the far bank races up and revs the engine to keep everything dry. We wade back across-our trousers soaked and our boots full of water. The boys from the village cross with us this time and we chat as we dry out on the far bank. The elder of the two says that it is 30km to the start of the asphalt. We clutch at this figure and make some futile calculations as to the chances of making it to Ouarzazate before nightfall. We leave our large map of Europe as a token of our gratitude and set off with everyone waving madly.

We are now on our first section of dirt road in Africa and follow the line of the river as it goes first east and later south and out of the mountains. We are at best going at 15m.p.h. The track has clearly not been used for some time which is a surprise as there are a number of villages along the way. We pass a few children who simply stare at us too stunned even to wave. As we go down a very steep hill strewn with boulders, we pass two girls themselves struggling with a donkey and cart. They wave and we continue to smile nervously. All the old doubts about the trip come to mind as the bikes grind along in first and second gear throughout the hot afternoon. The RS gearbox is not the world’s strongest and occasionally from deep inside the engine comes a loud bang. We struggle on making about 8 miles in the first hour from the river. When we stop some children rush out from nowhere and watch us consume an orange each. We are now low on biros to give away so instead give them some money as cadeaux.

Every so often we are forced to cross the river again. Each time it needs to be walked across first.

Only once do we get into real difficulties when the riverbed turns to sand and both bikes become bogged down. We mutter about not enough power and too much weight. The landscape changes constantly even though our progress remains very slow. At first as we run along the top of the river gorge it has sheer sandstone sides and there are fields and villages along the valley floor. Later the gorge widens and there are fewer fields but more sheep and goats feeding on sparse vegetation on the hills themselves. The colours deepen as the bright light of earlier begins to fade and about this time we reach the asphalt. Two kilometres later we realise why we have seen no cars. The main bridge has been completely washed away and there are no entry signs either side of the river. We talk to two locals as to how best to cross. One of them takes his shoes off and carries his bicycle across. The other with a moped shows us the best line and we cross the river for the last time in two stages resting on a sandbar halfway across. It is twilight by now and after we photograph the river and its sorry bridge we head out to the town still some 40kms away. The snowpeaked mountains are still clearly visible to the north but it is so warm that by the time we arrive in Ouarzazate we are both almost dry.

We find a hotel, shower and at 9p.m. try to find some food. All that is open a Café Touristique that is serving the ubiquitous tagine. We eat there only to find out that this was an error some 24 hours later.

Towards the Sahara

We do not linger in the morning but head out east to the start of the Valley of the Kasbahs – a long ribbon of road with walled citadel towns dotted along way. At lunchtime we detour to the north and follow a river bed back into the hills for some 20kms. Suddenly the river course backs up through a 500ft high gorge with a narrow valley floor. Although it is dry now the riverbed is strewn with enormous boulders which are washed down by the river in spate. There is a tourist cafe here and we have some coffee even though we are not representative of the clientele who are currently eating a banquet in full Bedouin style. As we drop back down to the main road, we are able to trace the limits of the town’s water supplies marked by a sharp end of the palm trees. We drive on through the stony plain until we reach Errachidia, the principal town in south-east Morocco. We drive on some 15kms until we reach the Source Bleu de Meski, an oasis with a large palmeraie close by an abandoned fort. The water source continually fills a swimming pool and showers and toilets are also served by and pipes from the spring. We camp there that evening and remain there the next day too. That evening we sit out and while I read and write some cards, Leigh goes off to try and work out more constellations than just Orion and the Great Bear under the pulsating canopy of stars. Leigh and I are talking to each other far more about ourselves by now. The novelty has worn off the trip and there is a sense of it as something longer and deeper is taking over. Conversation is no longer centered around the bikes and which route we will take and it is much more about what we are thinking about as we travel and about all the things that are so new and alien. At dawn I wander over to the old fort and later we take a route back into Errachidia. Here we wander around the low open town and buy food prior to our first meal using the gasoline powered stove. Like putting up the tents for the first time, we have avoided this moment for too long.

In the evening, we light the stove and prepare a vegetable stew and soup. We are using a dry-stone wall as a table and just as we are about to serve it up, I notice something by Leigh’s head as he is bent over the stove. I tell him to move away from the cooker and this he does. He then asks why and I shine the torch on to the wall where a small white scorpion is scurrying away from the light into a crack between the stones. We are both pretty surprised and shocked not having expected to see scorpions until after we had crossed into the desert itself.

The drive the next day brings home to us just how close we really are to the start of the desert. During our first two hours along the main road in Southern Morocco we see two cars. We stop at the first major town of the day and eat omelettes and drink tea in a tiny restaurant by the road. A considerable crowd has gathered around the bikes and before we leave we chat for a long time to a teacher who is travelling to work in Erfoud a town further south on the Sahara’s northern edge. As we continue east the land becomes hillier and even drier.

We are amazed to see a carpet of purple flowers which rolls back as far as a low range of hills off in the distance.

Later we run into a swarm of yellow insects. Leigh suggests that these are locusts while I insist wrongly that they must be grasshoppers.

We learn much later of the massive United Nations efforts to eradicate locusts in the Sahara and Sahel. The swarms extend over many square miles and we are forced to slow down and ride with our hands over our faces just to keep our teeth whole.

We reach Figuig and agree to stock up a little and cross into Algeria the next morning. Few people cross by this route and the town is not at all busy. We stumble around until a policeman points us in the direction of the town’s only restaurant. We sit there for the whole evening writing and chatting and half watching the Moroccan television. We watch more avidly when The New Avengers begins and Patrick MacNee appears discussing the finer points of cricket to Purdy in French. We retire culture shocked to our very Spartan and empty hotel.

If we had feared that entering Algeria would not be easy then leaving Morocco was not without its moments. I had a worrying half hour when a customs official realised my insurance documents were neither genuine nor valid. I was compelled to lie convincingly enough to be believed and although I don’t think I was believed we were allowed to go on. After that heart stopping moment, the Algerian border was simple enough. There were searches of our pockets and of our bags, silly questions and sillier forms to be filled in before we were allowed to drive up to the bank for the compulsory $160 money change each.